Submission

June 02, 2023

The Post New

David Attwood at Moore Contemporary, Perth, Australia

May 05 — June 03, 2023

* * *

* * *

In 1980, young artist Jeff Koons unveiled The New, his first solo exhibition in the window of the New Museum in New York: a series of pristine, off-the-shelf Hoover vacuums and carpet shampooers, housed in acrylic vitrines and backlit with cold, white fluorescent tubes. Shown in pleasingly symmetrical pairs, the domestic devices were transformed into objects of veneration. In their newfound institutional (yet nonetheless, street bound) context, they became legible both as artworks and as artefacts of consumerist desire. Koons had wholeheartedly taken up the tradition of the Duchampian readymade, but, before anything else, he was the son of a furniture dealer and interior decorator. The artist seized the languages of visual merchandising and museum display to set off the forms and contours of his machines, to put them on show. Their product names, which Koons appropriated as titles, reflected middle-class American aspirations towards glamour and luxury: ‘Celebrity’, ‘Deluxe’, ‘Convertible’.

He claimed these works formed part of a broader concern with the human condition, anthropomorphising them:

My work I believe is always directed toward what it means to be alive, what it means to be a human being in the world we live. And these are breathing machines. They are like individuals. And the first thing that we do when we come into this world to be alive is to breathe. [2]

Like people, they also had sexual qualities, both feminine and masculine, that apparently annulled one another:

I believe that the vacuum cleaner possesses both sexes […] they are machines that suck, therefore they have large holes […] but they also have phallic attachments. But I see them as a neutral sexuality […] [3]

Much like the pretty, chaste housewives who wielded them, he fetishised their unspoiled state:

These vacuums […] are like eternal virgins. They’re brand new. The object has its greatest amount of integrity before it ever participates in the world. Their cords are wrapped up just as they came out of the box. [T]hey’ve never been turned on. They’ve never participated. [4]

* * *

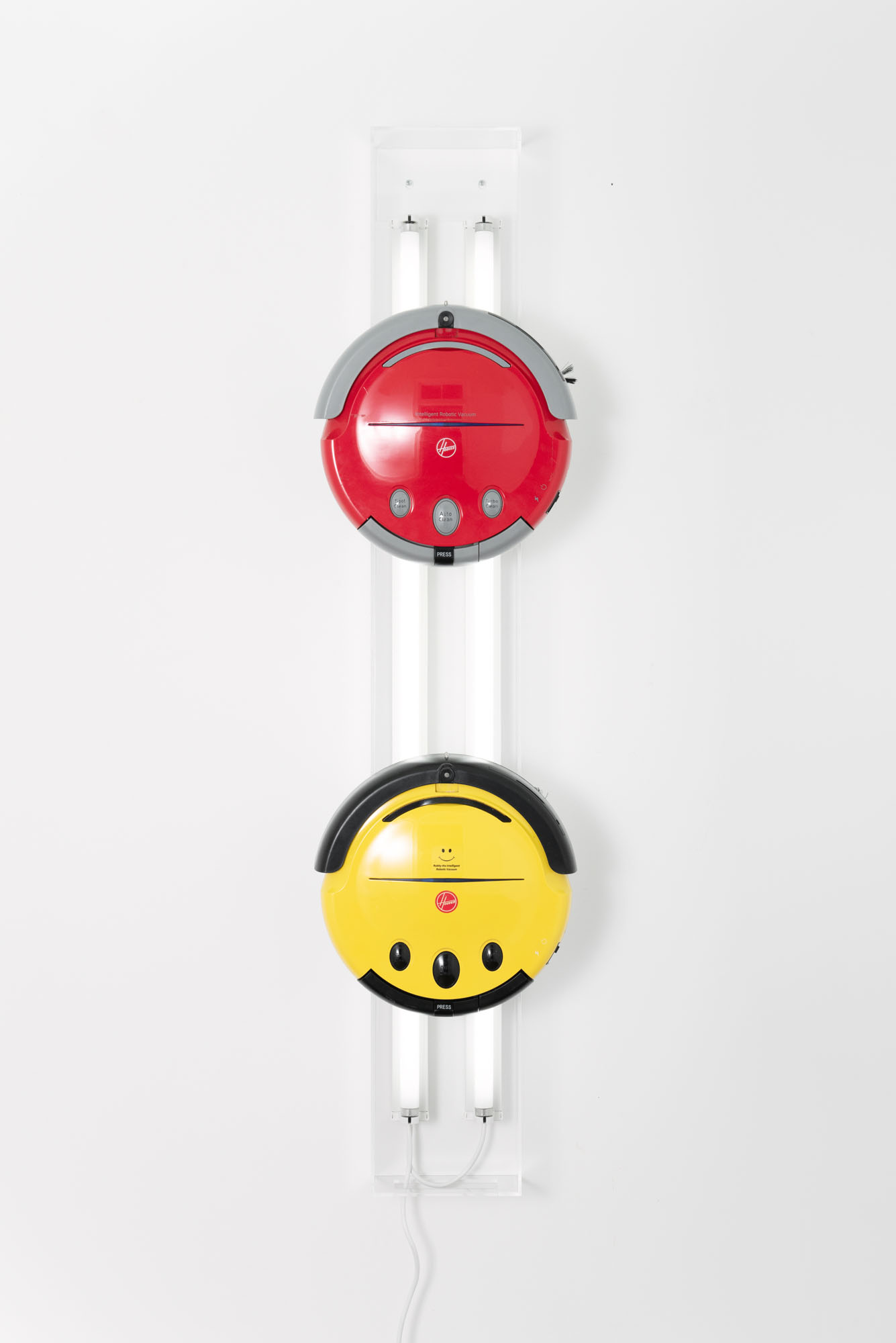

David Attwood’s The Post New presents vacuum cleaners that have well and truly inhaled the polluted air of late capitalism. Exploiting the same display method as Koons, but with twenty-first century models, the artist lays bare the cumulative impacts of their use. This is evidenced in the dirt and grime adorning their bodies, along with nicks, scratches, and repair attempts made over time. Attwood does not celebrate a perverse, idealised condition of newness, a myth that must be remade each time the breadwinner returns home. His vacuums are used up whores, fully expired (‘breathed out’). Time, therefore, is embedded in these objects, the chronic time of maintenance.

Ironically, maintenance labour is performed well when it leaves no trace. As such, the works memorialise the invisible labour performed by domestic workers, cleaners, caregivers and caretakers, that enables all other economic activity to take place. And what of the visibility of the grime itself? Attwood draws attention to the shifting relations between interior and exterior – the abject versus the decorous – in the last two centuries, that is strangely echoed in vacuum design. While dirt is directed to an opaque or concealed dust bag in early iterations, in more recent models filth is exposed via transparent barrels or chambers. In her 2011 article, architectural theorist Teresa Stoppani aligns this move with ‘the dismantling of the domestic interior in the 20th century, and […] re-conceptualisations of privacy, cleanliness and domestic economy’. [5] But, she maintains, this transition is only made possible through the management and containment of domestic debris (I am reminded of Deleuze’s ‘control society’, [6] a form of governance that gives the impression of freedom and agency, while control is in fact consolidated). There is a kind of sick satisfaction derived from scrutinising the masses of grit and hair collected in these devices.

With the advent of the robot vacuum, dust is counterintuitively concealed again. These machines embody the promise of automation, pointing to the techno-utopian dream for the abolition of manual labour from industry. They are marketed so as to give the impression of complete autonomy, leveraging the language around artificial intelligence, and its mysterious, even magical, black-box functioning. Despite their inscrutable operation, these cleaning companions must be docile, cute even, as they buzz around our living rooms like obedient pets. Human is still master. The vacuums that Attwood uses clearly engage in this rhetoric, given models names like ‘Intelligent Robot Vacuum’, ‘Magic Stick’, and ‘Aura’. All this talk of liberation from physical labour, however, remains purely figurative. Though waste kept out of sight, apparently taken care of by your nimble servant, the reality is, it always misses a spot, is obstructed by the kids’ toys strewn across the floor, or gets clogged up with Gizmo’s fur.

* * *

Sprangler received a patent in 1908, and in the same year, William H. ‘Boss’ Hoover, a leather goods manufacturer looking to diversify, bought the design. The Electric Suction Sweeper Company was established, renamed the Hoover Suction Sweeper Company after Sprangler’s death in 1915, and, in 1922, shortened to the Hoover Company.

We know the appliance firm now simply as Hoover. In the UK, ‘hoover’ has entered daily parlance, referring both to the act of vacuuming and to the cleaning device itself. No one remembers Spangler, weary and wheezing, labouring over the carpeted expanse of Zollinger’s Department Store.

— Stephanie Berlangerie, 2023

[1] Maintenance’ is a term used by curator Helen Molesworth, who herself borrows the concept from the artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles. In the 1970s, Ukeles’ staged a series of performances she classified as ‘Maintenance Art’, in which she cleaned and cared for private and public spaces, drawing a link between the underrecognised work that takes place at home (usually by women) and that which supports the functioning of institutions. Molesworth adopts the word to emphasise the equivalence of these forms of labour, resisting the minimisation of domestic work, and assigning it its proper value. See Helen Molesworth, ‘Work Avoidance: The Everyday Life of Marcel Duchamp’s Readymades,’ Art Journal, vol. 57, no. 4, 1998, pp. 50–61.

[2] https://whitney.org/collection/works/7399

[3] Koons qtd. in Teresa Stoppani, ‘Dust, vacuum cleaners, (war) machines and the disappearance of the interior’, idea journal, vol.11, no. 1, pp. 50-59.

[4] https://whitney.org/collection/works/7399

[5] Stoppani, p. 51.

[6] Gilles Deleuze, 1992, ‘Postscript on the Societies of Control’, October, 59, pp. 3–7.

The Post New

David Attwood

Moore Contemporary, Perth, Australia

May 05 — June 03, 2023

Text: Stephanie Berlangerie

Photography: Dan McCabe

David Attwood (b. 1990) produces sculptural assemblages, readymades and found-objects using contemporary commodities. His work broadly explores concepts pertinent to contemporary capitalism, such productivity, entrepreneurialism and automation, and extends into independent modes of exhibition making.

In 2016 Attwood completed a PhD in Art at Curtin University, and in 2019 completed the SOMA Summer program, SOMA, Mexico City. He has participated in numerous solo and group exhibitions nationally and internationally in institutional, commercial, artist-run, online and offsite settings. Attwood is the co-editor of the book The Art of Laziness: Contemporary Art and Post-work Politics (Art + Australia, 2020) and runs the project space Disneyland Paris.

O FLUXO is an online platform for contemporary art.

EST. Lisbon 2010

Follow us:

@instagram

@facebook

O FLUXO

© 2023