[aesop_content color=”#ffffff” background=”#ffffff” width=”93%” columns=”2″ position=”none” imgrepeat=”no-repeat” floaterposition=”left” floaterdirection=”up” revealfx=”off”]

[/aesop_content]

[aesop_content color=”#ffffff” background=”#ffffff” width=”93%” columns=”4″ position=”none” imgrepeat=”no-repeat” floaterposition=”left” floaterdirection=”up” revealfx=”off”]

David Attwood

Officeworks is an exhibition that I organised inside of an Officeworks department store in Fremantle, Western Australia.

I invited artists Daniel Eatock, Sean Peoples, Shannon Lyons and the artist group Greatest Hits to each contribute a work for the show that I would install or perform on their behalf. The show was not approved by Officeworks, and to the best of my knowledge it took place without their knowledge. The show was not advertised to the public to attend, but was instead documented with the view that it would exist as an exhibition catalogue that would then be shared online. Along with the artists I invited to participate in the show, I also asked two writers Taylor Reudavey and Francis Russell to contribute to the catalogue and do the heavy lifting to contextualise the show in relation to contemporary notions of work.

I came up with the idea of putting on a show inside of an Officeworks store because I thought that it might in some way to speak to some similarities between the work of the contemporary artist and the work of the office worker, and that this might, by extension, say something about the efficacy of contemporary work in general. I had been reading The Refusal of Work: The Theory and Practice of Resistance to Work (2015) by David Fayne who talks through the work-centric nature of contemporary western culture, and what he sees as an increasing hostility toward the human need for autonomy, leisure and community under capitalism. The book made me feel good about myself momentarily –‘I’ve got a good life-work balance. Work part time and I work the rest of the time.’ The truth is that I Work part time at a University, so when the Work is over for the year and the 12 week summer begins, this period can be both financially and emotionally difficult. Having only some work to do and no Work to do, and so without having to be anywhere Monday through Friday is good for a while, but eventually makes me feel a bit like I’m not doing anything. The way that I dealt with this last summer was by inscribing short statements on paper towels with texta pens. I called this series Doldrums and the short texts read things like ‘Today’s Sunday David Attwoodtomorrow’s Sunday too’ and ‘I need a new series’. The way that I dealt with the doldrums this summer was to organise a show inside of an Officeworks.

The last chapter of Fayne’s The Refusal of Work includes a series of interviews with people living in the UK who are actively resisting work by choosing to work less, or not at all, in favour of pursuing other activities or forms of leisure such as gardening or train modelling. (Is my practice their train modelling?) Fayne uses the familiar example of being asked ‘So what do you do’ shortly after being introduced to a stranger as a means to illustrate the way that societal pressures work to align one’s identity with one’s occupation. For those resisting work the prioritising of their preferred leisure activity acts like a proud reprieve from this social trap.

Negotiating and or evading the ‘So what do you do’ question at a social gathering is always a humorous talking point amongst my peer group of fellow artists. A friend recently posted a meme of a blurry Principal Skinner hastily escaping through an open window with the caption ‘When you get introduced as an artist at Christmas’. Typically, it is agreed that explaining to the stranger that you are an artist inevitably leads to further questions regarding the type of artwork you make, which can be tricky and tedious terrain and so it is best to avoid this altogether. But perhaps a genuine reason for not plainly answering this question with ‘I’m an artist’ is because there is a scepticism as to whether this is real Work, both in the imagined opinion of the stranger that I assume will be unsympathetic, but maybe also in the deep down opinion of me, the artist.

A podcast titled Status Effect curated by artist Andrew Varano recently featured a piece by artist Max Grau titled ‘reclaim your fucked-up-ness… maybe’ (2016). Speaking in the first person (through the guise of an appropriately monotone voice actor) Grau talks about spending the whole day in bed and the associated guilt that this can often conjure. Grau asks “As an artist why do I feel like a failure when I spend the day in bed instead of like an avant-gardist?… Why do I tell my friends that I was doing office stuff all day instead of proudly admitting that I watched half a season of Buffy the Vampire Slayer? Why do I worry about being considered lazy? When did I become so professional and if that’s the case why do I earn so little money?”[1]

Grau relays a friend of a friend’s story about a ‘quite well known’ artist complaining about being stuck in LA traffic on the way to their studio. One day the successful artist realises that they are just one more guy commuting to work and that their practice had become a regular job. “Well, it doesn’t have to be” Grau states, with poise. ‘reclaim your fucked-up-ness… maybe’ ends with a manifesto-like affirmation to dismiss the guilt of laziness and embrace the special working conditions of the artist.

The refusal to participate in the neoliberal mess that is our everyday life is hard to keep up these days. Not a lot of people seem to think that there is still some kind of outside. But like, as artists don’t we kind of produce fiction for a living? …If you’re fucked up use the means of artistic production to address exhaustion on a level that is more complex than doing a spa day once in a while. Invent ways to talk to your friends. Fucking start considering your colleagues as friends. Blame capitalism not yourself. Instead of worrying if you might be working too little start asking if they might be working too much. Have a sip of champagne in bed even when you’re alone.[2]

I think David Frayne would approve of this attitude, and I feel better.

I had originally thought that putting on a show inside of an Officeworks might in a humorous self-deprecatory way invite an equivalence of sorts between the contemporary artist and the office worker; both spend time in a small room at a computer, typing, editing, ordering, purchasing, accounting, promoting in between scrolling facebook and refreshing gmail. Perhaps subconsciously this was a strange attempt to legitimise the work of the artist, aligning this mode of work with more familiar, recognised and socially accepted forms. In this world being introduced to the stranger at the party as an artist would be just as uninteresting as being introduced as an office clerk, or a teacher etc.

I know feel that maybe it is more the differences that legitimise and provide value for the work of the contemporary artist. Liam Gillick’s essay ‘The Good of Work’ (2011) begins with an accusation that under the current neoliberal conditions of western culture, or what he describes as the “predatory neoliberal regime”, artists have become the ultimate freelance knowledge workers. “Artists are people who behave, communicate, and innovate in the same manner as those who spend their days trying to capitalize every moment and exchange of daily life. They offer Shannon Lyons Constellation (Don’t Go Now) 2016 Cast polymer plaster, ink.no alternative to this.”[3] Gillick later provides a series of musings on ways of combatting this accusation in tangentially addressing the good of work. When isolated some of these points read like studio aphorisms “working less can result in producing more” and “as there are no limits to work there are also no limits to not working.” A point that seems particularly poignant to my thoughts on the impetus for Officeworks and the artist/worker dual reads “The reason it is hard to determine observable differences between the daily routines and operations of a new knowledge-worker and those of an artist is precisely because art functions in close parallel to the structures that it critiques.”[4] The Officeworks show as Trojan horse.

Another of Gillick’s points seems to nicely echo Grau’s sentiments on working from bed, watching Buffy and drinking champagne.

Not thinking about art while making art is different to not thinking while preparing a PowerPoint presentation on the plane. Of course I am working even when it looks as if I am not working. And even if I am not working and it looks as if I am not working I still might claim to be working and wait for you to work out what objective signifiers actually point towards any moment of value or work. This is the game of current art. Art production and work methods are not temporally linked or balanced because the idea of managing time is not a key component of making art, nor is it a personal or objective profit motive for artists. Unless they decide that such behavior is actually part of the work itself.[5]

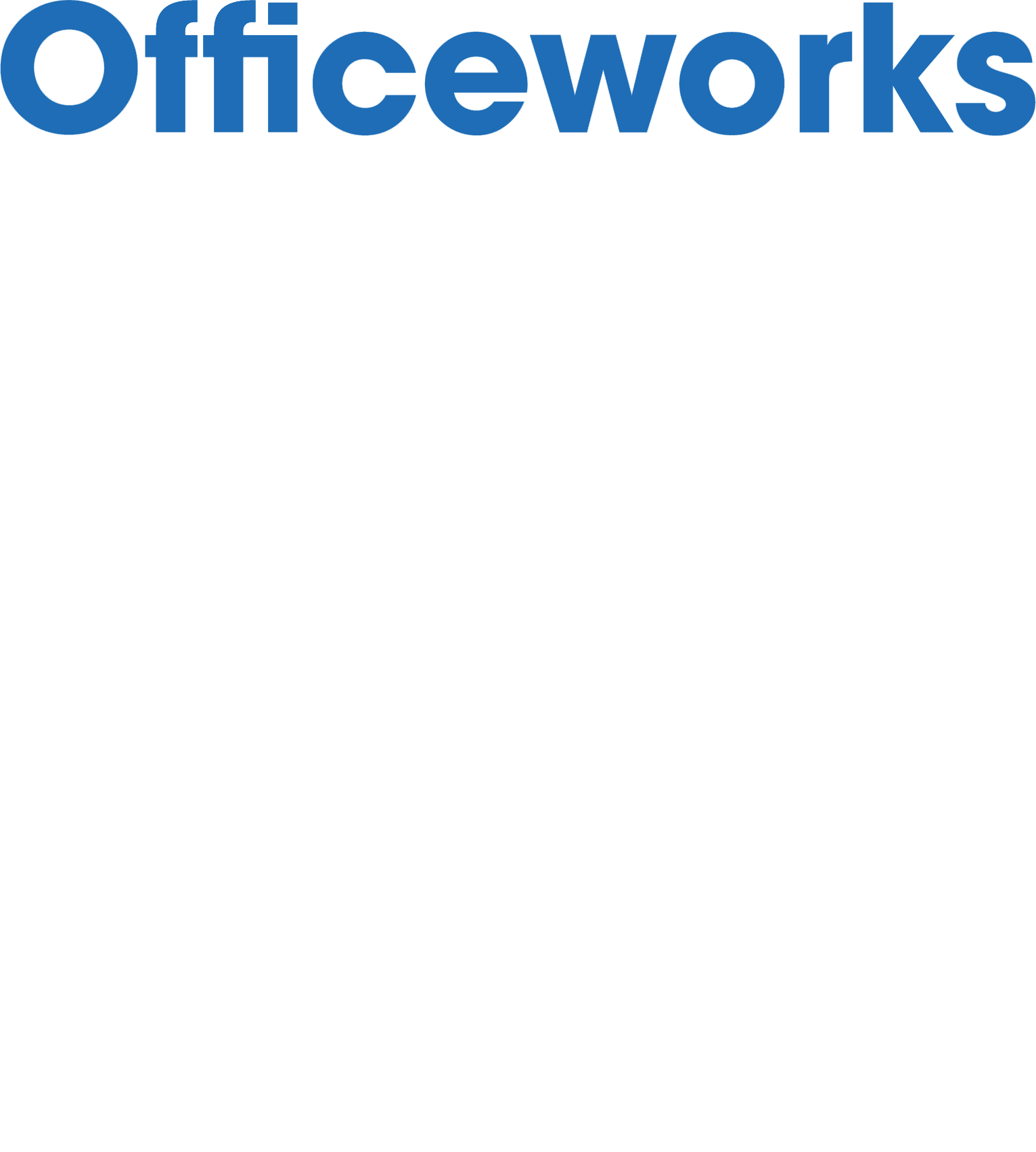

I guess it’s logical that if art has become what ever the artist says it is, the same must apply to their work. I wonder how many of the artists I asked to contribute to Officeworks conceived their work while doing other things. I didn’t and still don’t know LA based artist Daniel Eatock when I sent him a ‘cold’ email inviting him to participate in the show. He promptly replied with a one-line instructional statement; ‘Try every pen in the store with a scribble on one piece of paper.’ The promptness and efficiency of his reply makes me suspect that he was already online, perhaps in bed, perhaps watching Buffy.

I have decided to not disclose much here about the artists involved in Officeworks and the nature of the works they have made for the show. These are presented in their image-form within this catalogue more generously than I can describe them, and I’d prefer to leave them open to a multiplicity of readings. I consider the premise of the show an artwork in itself, one that attempts to collaboratively pose questions with an audience rather than provide answers to a consumer. I am particularly fond of artworks that have the ability to be distilled down into a single sentence that can then be easily disseminated through conversation, traded and exchanged like a business card. A collaborative artwork in the form of show that occurred unannounced within an Officeworks store conjures a nice image.

[/aesop_content]

[aesop_content color=”#ffffff” background=”#ffffff” width=”93%” columns=”1″ position=”none” imgrepeat=”no-repeat” floaterposition=”left” floaterdirection=”up” revealfx=”off”]

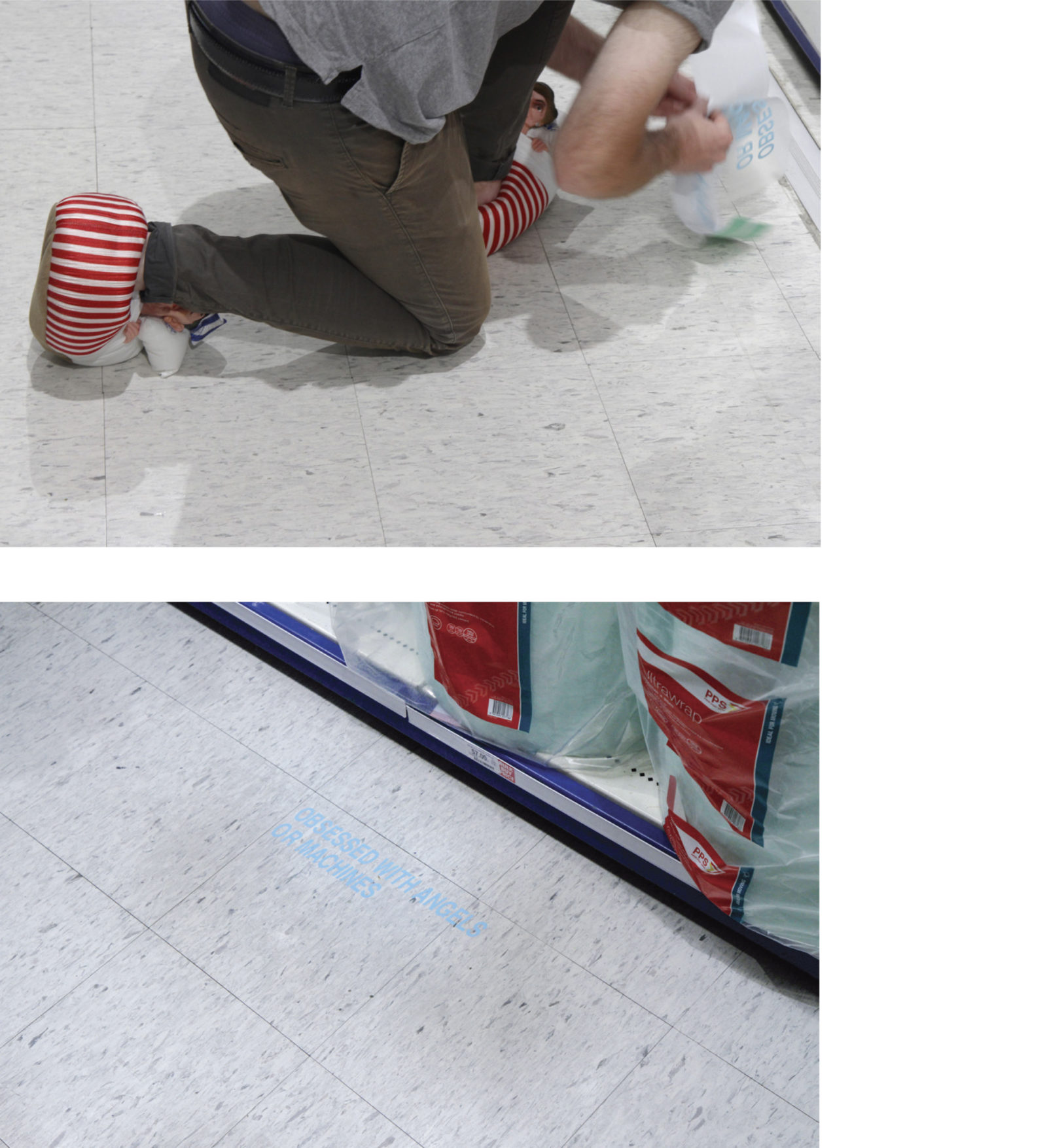

Gavin Bell, Jarrah de Kuijer & Simon McGlinn (Greatest Hits)

Political slippers worn by curator installing artwork

2016

Vintage Ronald & Nancy Reagan slippers, curator.[/aesop_content]

[aesop_content color=”#ffffff” background=”#ffffff” width=”93%” columns=”1″ position=”none” imgrepeat=”no-repeat” floaterposition=”left” floaterdirection=”up” revealfx=”off”]

Daniel Eatock

Pen Tests

2016

A4 paper,

scribble from 460 pens

[/aesop_content]

[/aesop_content]

[aesop_content color=”#ffffff” background=”#ffffff” width=”93%” columns=”1″ position=”none” imgrepeat=”no-repeat” floaterposition=”left” floaterdirection=”up” revealfx=”off”] [/aesop_content]

[/aesop_content]

[aesop_content color=”#ffffff” background=”#ffffff” width=”93%” columns=”2″ position=”none” imgrepeat=”no-repeat” floaterposition=”left” floaterdirection=”up” revealfx=”off”]

David Attwood

A reprieve in the form of an oaf

2016

A watermelon is smuggled into an Officeworks

store undetected by staff and left on the floor of an aisle.

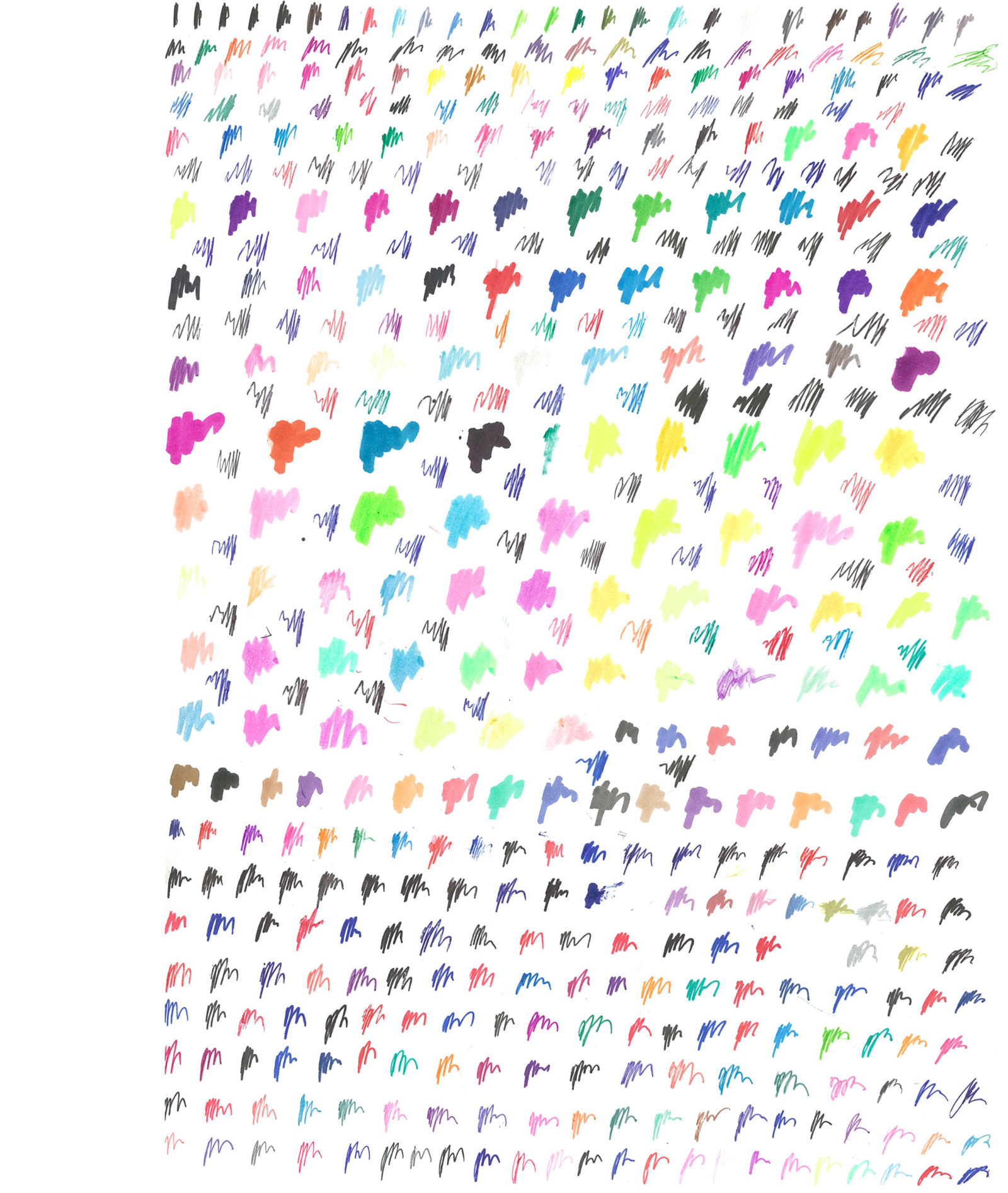

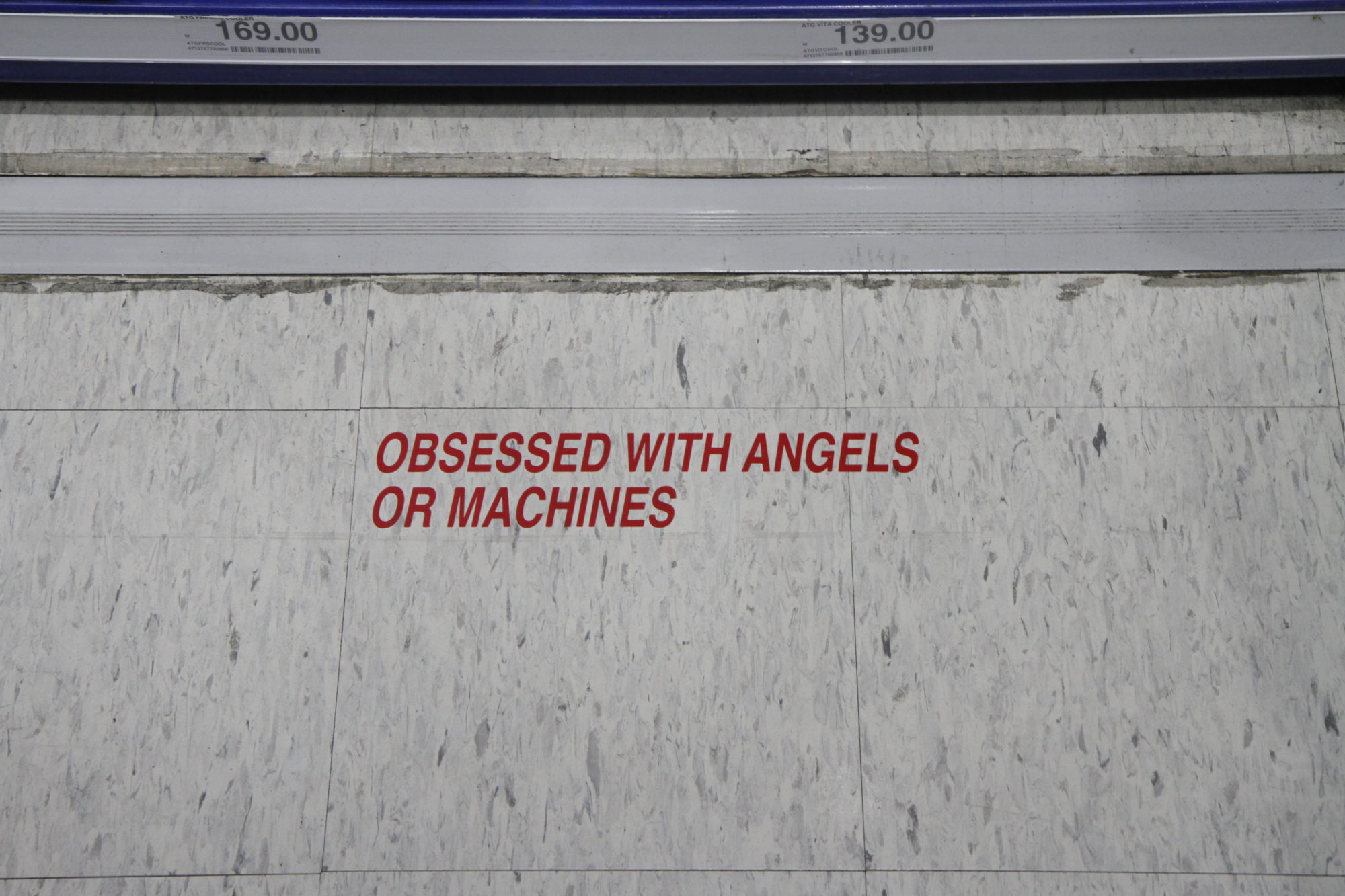

Sean Peoples

OBSESSED WITH ANGELS OR MACHINES

2016

Adhesive vinyl

Sean Peoples is represented by Station

[/aesop_content]

[aesop_content color=”#ffffff” background=”#ffffff” width=”93%” columns=”1″ position=”none” imgrepeat=”no-repeat” floaterposition=”left” floaterdirection=”up” revealfx=”off”] [/aesop_content]

[/aesop_content]

[aesop_content color=”#ffffff” background=”#ffffff” width=”93%” columns=”2″ position=”none” imgrepeat=”no-repeat” floaterposition=”left” floaterdirection=”up” revealfx=”off”]

Shannon Lyons

Constellation

(Don’t Go Now)

2016

Cast polymer plaster, ink.[/aesop_content]

[aesop_content color=”#ffffff” background=”#ffffff” width=”93%” columns=”1″ position=”none” imgrepeat=”no-repeat” floaterposition=”left” floaterdirection=”up” revealfx=”off”] [/aesop_content]

[/aesop_content]

[aesop_content color=”#ffffff” background=”#ffffff” width=”93%” columns=”3″ position=”none” imgrepeat=”no-repeat” floaterposition=”left” floaterdirection=”up” revealfx=”off”]

Taylor Reudavey

In The Good of Work (2011), Liam Gillick acknowledges that artists are currently operating within a predatory neoliberal regime that is characterised by a neurotic, all-consuming work ethic and a shift towards the “rampant capitalisation of the mind”. Given the artist cannot work autonomously from this regime, their labour is open to being reduced to that of the ultimate freelance knowledge worker. Gillick responds to this perceived proximity between artist and entrepreneur by focusing on the production of art rather than its consumption as the site where the differentiation can be re-strengthened. Although the day-to-day work of the artist shares some superficial similarities to that of the office worker (i.e. emailing, invoicing, writing to-do lists, procrastinating, and so on), Gillick reminds us that art functions as a system of awareness and creates new spaces for critical speculation, where artists are not obliged to present products or results and can instead raise more questions than answers, and their relationship to the viewer is one of side-by-side observation and reflection rather than the face-to-face honing in on a potential market demographic that characterises the relationships formed by the knowledge worker.

Artists are relatively free to reshape the nature of production as well as potential terms of engagement (and disengagement), in the hope of finding a better model to replace the old ones. The search for this, according to Gillick, is the titular “good of work”, the reason to keep working as an artist within the given system that is constantly absorbing and mutating beyond the artist’s control; hopefully there is some potential in work that is generative rather than results-based, that does not posit an easily measurable or pre-determined notion of success as its sole desirable outcome.[1]

Officeworks is an unusual approach to the production and dissemination of art, and although it may seem a little pessimistic or futile at first, it raises some interesting questions regarding the value of artistic labour and the relationship the artist has with their (public) audience. Here, the artists quietly defied the expected behaviours of the Officeworks shopper and held a fleeting show within the outlet, a self-acknowledged “illegitimate” venture in the sense that it was not approved by Officeworks at any level, but also in that it was not advertised or facilitated by the usual avenues in Perth’s art scene. There is certainly an element of stealth in the gestures themselves, though this is in play with some degree of conspicuousness: enough to be read as out of place, and in most cases, dealt with, but nothing that would raise any serious alarm.

Perhaps the question of legitimacy also reflects the anxieties the artist may hold in relation to their own work. Indeed, the gestures performed here seem to comically affirm such labour anxieties, particularly with regards to working in the public realm: objects are made to be left behind, and most likely discarded; gestures occur live in front of an audience that either doesn’t notice them or doesn’t appreciate them as carefully considered and performed artworks; and there seems to have been no documented attempt to engage in dialogue with the audience, almost with the expectation that they would have nothing interesting to say.

This could be seen as a kind of active withdrawal from the obligations of the public artist: firstly, a modest amount of material labour has gone into these gestures, on a small and inexpensive scale; secondly, given the rundown state of Fremantle Officeworks, the artists have refrained from assigning the purpose of their work as “rejuvenating” and “activating” the space, which is what most funded public artworks seem to ask for (particularly given the current prevalence of social media, with its ability to outsource marketing, generate hype and encourage economic activity in the area). Perhaps it is also an active withdrawal from the expectations of social practice: a comparatively loose relationship with the viewer is being proposed here, with no pre-determined function of the audience as participants or grateful recipients. The audience is there, but the purpose of the work doesn’t rest on them; they are given the agency to respond, but the artists (and their cameras) have already left the building. This is not to say that they are outright rejected as a component of the artwork, otherwise these gestures could have been performed anywhere, in front of anyone (or no-one). Situating these gestures in Officeworks refers back to the proximity between the artist and the knowledge worker that Liam Gillick speaks of, and although the gestures themselves reaffirm the differences and lack of dialogue between them, it doesn’t take a we’re-not-them-so-let’s-not-think-about-them approach. Officeworks confronts the anxiety of work and explores the potential for redefining how artists engage with their audience, away from the relative safety of the gallery with its generally appreciative viewer and beyond the function and perception of public art as it stands today. We could say that such redefinitions open up new ways for the artist to approach their work, for the public audience to appreciate work and the multitude of roles it can play in their lives. Perhaps it even allows for the beginning of some kind of solidarity with the knowledge worker in the face of the given circumstances, if we are to be really optimistic. Such questions about labour, and how we might value and perceive labour, are worth pursuing through the artist’s work.

[/aesop_content]

[aesop_content color=”#ffffff” background=”#ffffff” width=”93%” columns=”2″ position=”none” imgrepeat=”no-repeat” floaterposition=”left” floaterdirection=”up” revealfx=”off”] Gavin Bell, Jarrah de Kuijer & Simon McGlinn (Greatest Hits)

Gavin Bell, Jarrah de Kuijer & Simon McGlinn (Greatest Hits)

Political slippers worn by curator installing artwork

2016

Vintage Ronald & Nancy Reagan slippers, curator.

Shannon Lyons

Shannon Lyons

Constellation

(Don’t Go Now)

2016

Cast polymer plaster, ink.[/aesop_content]

[aesop_content color=”#ffffff” background=”#ffffff” width=”93%” columns=”1″ position=”none” imgrepeat=”no-repeat” floaterposition=”left” floaterdirection=”up” revealfx=”off”] [/aesop_content]

[/aesop_content]

[aesop_content color=”#ffffff” background=”#ffffff” width=”93%” columns=”3″ position=”none” imgrepeat=”no-repeat” floaterposition=”left” floaterdirection=”up” revealfx=”off”]

Francis Russellwork

Imagine, for a moment, that a medieval craftsman comes to the future and visits an Officeworks store. Bracketing the various impossibilities that would prevent such an occurrence, we could nevertheless imagine a state of absolute wonder as the craftsman in question looked on at aisle after aisle of furniture, pens, notebooks, and paints – not to mention computers, cameras, etc. Indeed, Officeworks not only provides us with an array of artistic materials, but, moreover, could be seen as a museum of contemporary media – print, digital, traditional, contemporary, etc.

Officeworks sells cheap media. Whereas our medieval craftsman would have encountered a word where forms of mediation such as ink and paper would have been incredibly rare, if one wants to write a poem, produce a drawing, make a sculpture, produce an animation, and so on, one could find everything they need and at a fairly affordable price. The question then becomes what makes such a space so mundane? Why is it that Officeworks does not suggest itself as a treasure-trove of possibility?

What makes the space seem so profoundly dull and unremarkable? One possibility would be that a certain art of paying attention is necessary for any of the above possibilities to come into fruition. For example, for less than $3 I can find all the means to produce a book of poetry – imagine the look on the medieval craftsman’s face! – and yet in order to have anything to write about I would need to have at the very least learned to pay attention to something. This art of paying attention is not necessary easy to acquire, teach, and celebrate.

While I can find the material needed to support an artistic practice for a handful of dollars, the education required (though it need not be acquired formally) to pay attention to something is not necessarily something that is cheap or timely.

To take the gallery and the Officeworks store together, one could wonder if either work or art would be recognisable if one were to pay attention. By this I don’t mean that if one were able to pay attention they would no longer recognise work and art in the contemporary world – as if these two phenomena, art and work, had lost there way and become unrecognisable because of a loss of essence. No, instead the question is whether or not paying attention would cause us to question how we are so assured that we know what we are dealing with when we enter the gallery or store. Officeworks presents materials for the contemporary worker – again, pens, books, laptops, furniture, etc – but what is it that contemporary workers do?

What and who is their labour for? What is it that they produce – i.e., what are the works for and of the office that Officeworks stockpiles and sells? Similarly, what and who is art for? Other than belonging to a specific space – the white cube or similar institution – what relevance does contemporary art have?

Rather than seeking an answer to these questions, the issue at hand is one of why these questions so rarely appear – or if they do appear, why is it that they so rarely appear as genuine questions, as opposed to defensive accusations formed deceptively in the interrogative? In light of this problem, the works in this exhibition are traces of various artistic practices that attempt to privilege the importance of paying attention – paying attention to art, Francis Russellwork, and their intersection in the contemporary world. Indeed, as Dave Attwood has stated himself, the premise of this collection of interventions could very well be seen as the main work. Taken collectively, or even with regards to the individual pieces that it is comprised of, this aesthetic intervention serves as an opportunity offered, the opportunity to pay attention in those contemporary spaces situated at the nexus of banality and possibility; at the nexus of that which we are assured in overlooking, and that which we can pay attention to.

Shannon Lyons’ contribution gestures towards the question of the counterfeit, absence, and the unknown that potentially lurks behind every given. In carefully remaking what is conventionally taken as a mere background support her work hints at an invisible world that hides in plain sight. Daniel Eatock’s work challenges the commodification of attention through the contemporary valorisation of mindfulness. In instructing the curator to test every pen in the store, the artist raises important questions about the commodification – the repackaging and selling – of our most basic capacities to pay attention – to see what reveals itself when we reflect on the overlooked character of the mundane. Dave Atwood’s contribution raises questions about the expectations that colour our sense of what belongs in a specific space. By introducing a watermelon into the austere environment of an Officeworks store he poses the problem of what it is that frames our sense of place in a world of increased standardisation and homogeneity. Sean Peoples’ work makes literal the notion of a poetics of the banal and everyday, inserting fragments of verse onto the floor of a well-trodden path. Finally, the work of Greatest Hits reminds us that we walk around with the political implication of past eras. The neoliberal policy so espoused by figures like Reagan, and the defunding of arts and humanities education under various western neoliberal governments, has had an enormous impact on our capacity to pay attention. If paying attention, as we have discussed it here, can only be understood in monetary terms it will surely be lost – discarded as a practice as archaic as those of our aforementioned medieval craftsman.

All of these works, and the show itself as a work, are minimal in their capacity to impact some pre-existing state of affairs. Nevertheless, it is in their capacity to offer the viewer a place in the adventure of paying attention – paying attention to what is overlooked, unexpected, or marginal – that they find their worth. To modify a famous quote by Søren Kierkegaard, the function of paying attention is not to discover the truth of a world static and ready-made, but rather to change the nature of the one who pays attention.

[/aesop_content]

[aesop_content color=”#ffffff” background=”#ffffff” width=”93%” columns=”2″ position=”none” imgrepeat=”no-repeat” floaterposition=”left” floaterdirection=”up” revealfx=”off”]

David Attwood

Daniel Eatock

Greatest Hits

Shannon Lyons

Sean Peoples

Writing by

David Attwood

Taylor Reudavey

Francis Russell

Layout based on

Design by

Celeste Njoo

All images courtesy of the artists.

Photos of Greatest Hits and Sean Peoples by Lance Ward.

[/aesop_content]