OFLUXO

Foulplay

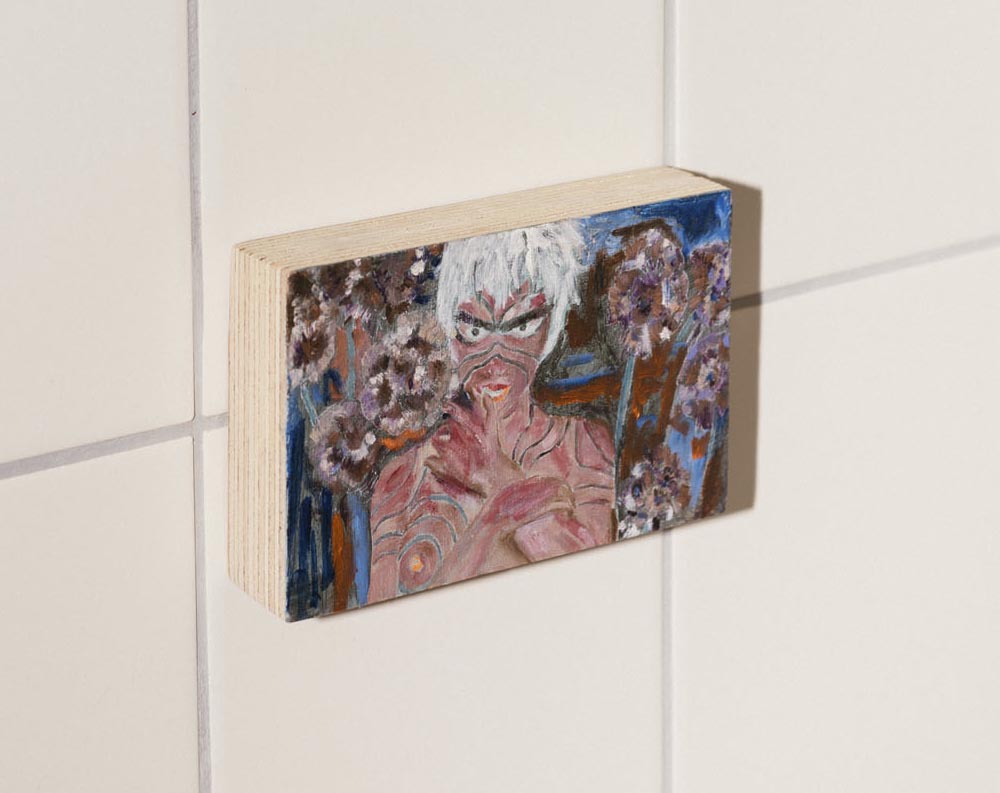

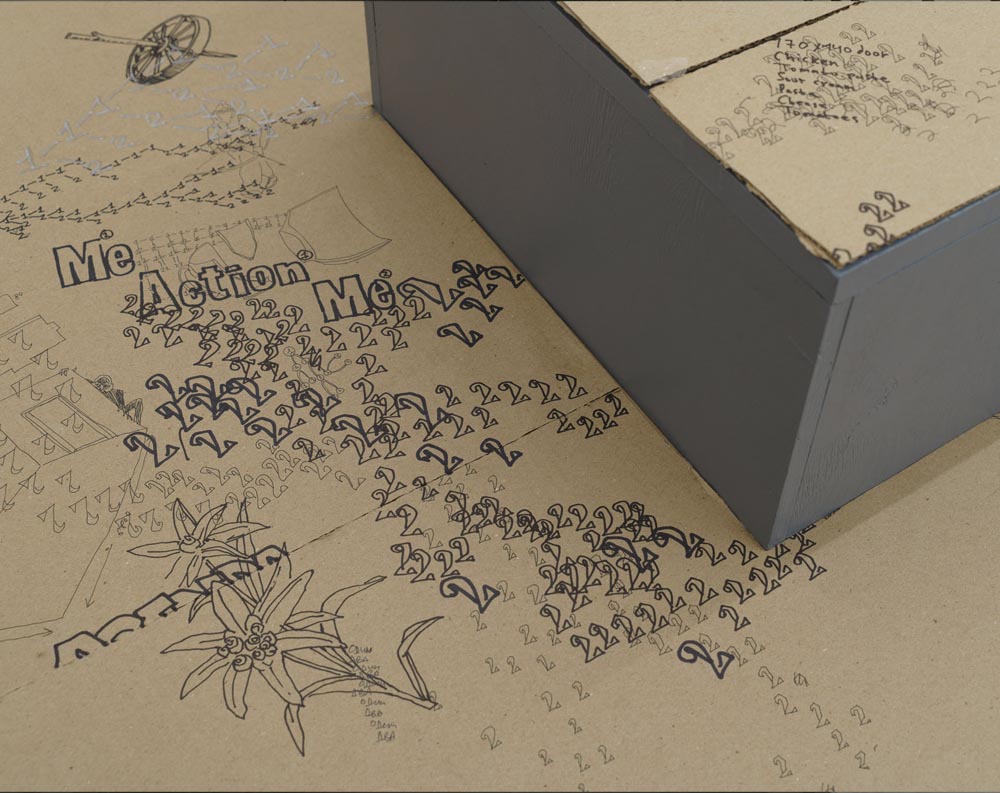

Laura Gozlan

At Galerie Valeria Cetraro, Paris, France

March 12 — April 30, 2022

Photography by Salim Santa Lucia

When we examine Laura Gozlan’s latest works, and specially her films, we are tempted to relate her to the post-Exoticist movement, an artistic and literary movement that emerged at the end of the 20th century. Even when it is not absolutely clear who claims to be part of this movement, or even what it entails, it is still possible to list its main exponents —whether they be the authors of authentic works or be quoted in those publications. The list can include Antoine Volodine, Manuella Draeger, as well as Rebecca Wolf or Sonia Velazquez, the former citing the latters’ works. What we can say about Post-Exoticism, without much too boring paraphrasing, is a verifiable fact: only authors claiming to belong to the movement dare to define what they understand by Post-Exoticism. We can also say that even if its definition seems quite blurry and its contours fluctuate according to what may be convenient to a certain author when developing their narrative, it is almost certain that Post-Exoticism is not an opportunistic tautology but rather carries the ambition of a political project. A project that seems to be drawing the contour of a possible present, by describing it in the most distorted, phantasmatic manner possible and by being careful not to crystallize the movement’s ideas through an allegory or a metaphor. Post-Exoticism is revolutionary in that it drastically turns away from the real in order to figure out an alternative. As Manuella Draeger points out, “we are unable to say anything about whether it deals with a phantasm, the memory of a dream or a real biographical element”. Post-Exoticism is not a peaceful territory but the theater of violent conflicts where armed battles take place between opposites unable to be reconciled —patriarchal capitalist powers against secret societies, rhizomatic and convoluted, trying to overthrow them. What does exactly mark the affinity between Post-Exoticism and the rather elliptic narratives in Laura Gozlan’s films? Is it the difficulty to ascribe them to a genre —grotesque, horror, erotic, prophetic, oneiric — or is it their subversive content? Laura Gozlan’s films document a world we may refer to as parallel, that seems to be very near the one we inhabit but probably located in a cavity on the outside or below our visibility level. In that cavity hides a recurrent solitary character: Mum, a middle-aged woman whose features change from film to film as if alluding to different times in her life, unless she is subject to sudden aging or rejuvenating episodes. Slowing down her cells aging process is actually one of her main obsessions. This obsession leads her to guzzle down the juice from a mummy directly out of a sarcophagus using a straw, as well as to inhale and exhale vapors —that we suppose are both delicious and poisonous— in and out of organ-objects that can look quite obscene according to the angle we view them from, in addition to other techno-fantasy artifacts proposing unprecedented articulations between nature and culture. Another one of her obsessions is sexual self-pleasure, often following her chemical raptures. Mum’s onanism does not imply withdrawal but rather engaging in an offensive against heteronormative productivism, a joyful and deviant threat against the forces of so-called “natural order”. Mum is either seen in a laboratory wearing an elegant skirt and blouse, or next to a fountain of youth with her hair unkempt. She delivers prophetic, sibylline messages in a voice that seems to come from beyond the grave. Is Mum Laura Gozlan’s alter ego, a phantasmatic wild avatar? The character’s grotesque appearance, made up like Cindy Sherman in her Disasters series, could confirm this hypothesis and hence “disguise the obscenity implied in an outpouring of biographical information when no Post-Exoticist technique can derealize it”.

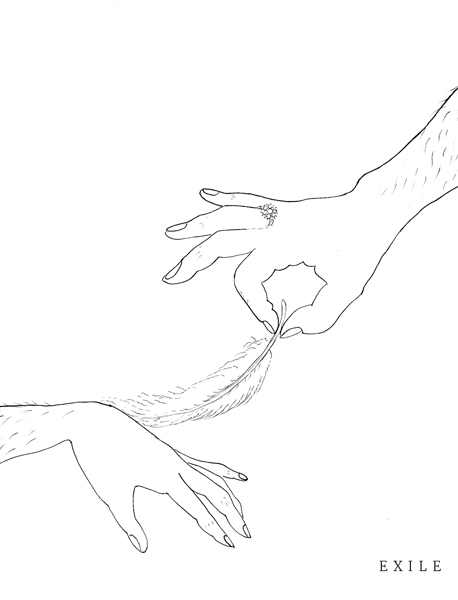

Foulplay, Mum’s new film, finds her down —an underground parking or the sewers– on the day after elections. Insurrection is in the air. At a moment when society could cross the line into a new world order, Mum receives a phone call from a mysterious character who summons her to transform the fascist threat into anarchic chaos through her magic sexual power.

“Neither Rebecca Wolf nor Sonia Velazquez”, explains Manuella Draeger in Herbs and Golems, “admit that a social imposture —backed by millions of years of animal abjection— leads girls, teenage, then adult and old women to honestly think and say that copulation is in no way disgusting but on the contrary that it is good for the body and the soul, essential to the way the world works and practically wonderful. (…) Without denying the obvious existence of female sexuality, both consider coitus to be tinged with blatant violence».

In Foulplay, Mum becomes a primitive deity. A seedy, sewage goddess. The incarnation of a separatist, masturbatory power which will unleash its revolutionary forces against patriarchy —a truly Post-Exoticist plan. Manuella Draeger confirms once again: “The ideal society according to Rebecca Wolf”, she writes, “the future society towards which egalitarians must work is austere, fraternal and free from a legacy of brutality. It is not a matter of orgasm nor reproduction.» Foulplay defines an illegal action, a crime. In Laura Gozlan’s film this term also has the connotation of filth and, literally, of scatological games — which also evokes the idea of radical self-sufficiency. But who befouls what?

— François Piron

Previous Articles

OFLUXO is proudly powered by WordPress