Gallery Fiction

by Natalya Serkova

Towards the new technology of art dissemination

I would like to begin with a simple question—are you sure that the exhibitions, the documentation of which you can daily observe on websites-aggregators dedicated to art, do exist in reality? I do not mean, of course, the projects that were initially realized online, but those that were created and documented in a traditional context of a “white cube” exhibition space, which has a specific physical location, say, in some particular district of Berlin. You know the area and you know the gallery, you might even personally know the curator who has put the show together, and yet the question still stands: are you sure that were you to step by the gallery at any given moment, you would be able to see this show in its actual physical form and in exactly the form and the shape in which you beheld it on your computer screen? The praxis of our memory, elaborated over the years of our life when we were confident that the connection between the real and the digital could be drawn somewhere on the territory of watching a yet another “Star Wars” episode, seems to be falling into unlikely traps now in places where we have not expected to encounter these traps.

Consider Adobe’s new program, which, obviously, will soon be available to everyone. It allows users to effortlessly delete and modify any object on the photo or video. To use it one does not need to be an expert in the field of photo editing, retouching and complex effects production. This means that the borderline between reality and fiction in the realm of any kind of visual documentation will inevitably shift from producing complex political falsifications, conspiracy theories and costly entertainment products towards a simple daily routine. Until recently, this routine could serve as a prop and a storage for individual memory, not unlike the pictures in family albums, carefully captioned by the father of the family in longhand. Such sentimentality will hardly vanish altogether, but it will mutate because the object triggering it is undergoing complex mutations itself. It will take a shape of a sentimental recollection not of the past lost irretrievably, but of the time that can be restored and rebuilt at any moment. It will be a recollection of the future and it will merely take a desire and a simple effort to will this future into reality. Digital presence is gradually giving way to the analogue one, and this substitution expands rather than destabilizes the possibilities of our mind, with its one “foot” in the Paleolithic age and the other “foot” hitting the gas of racing simulators.

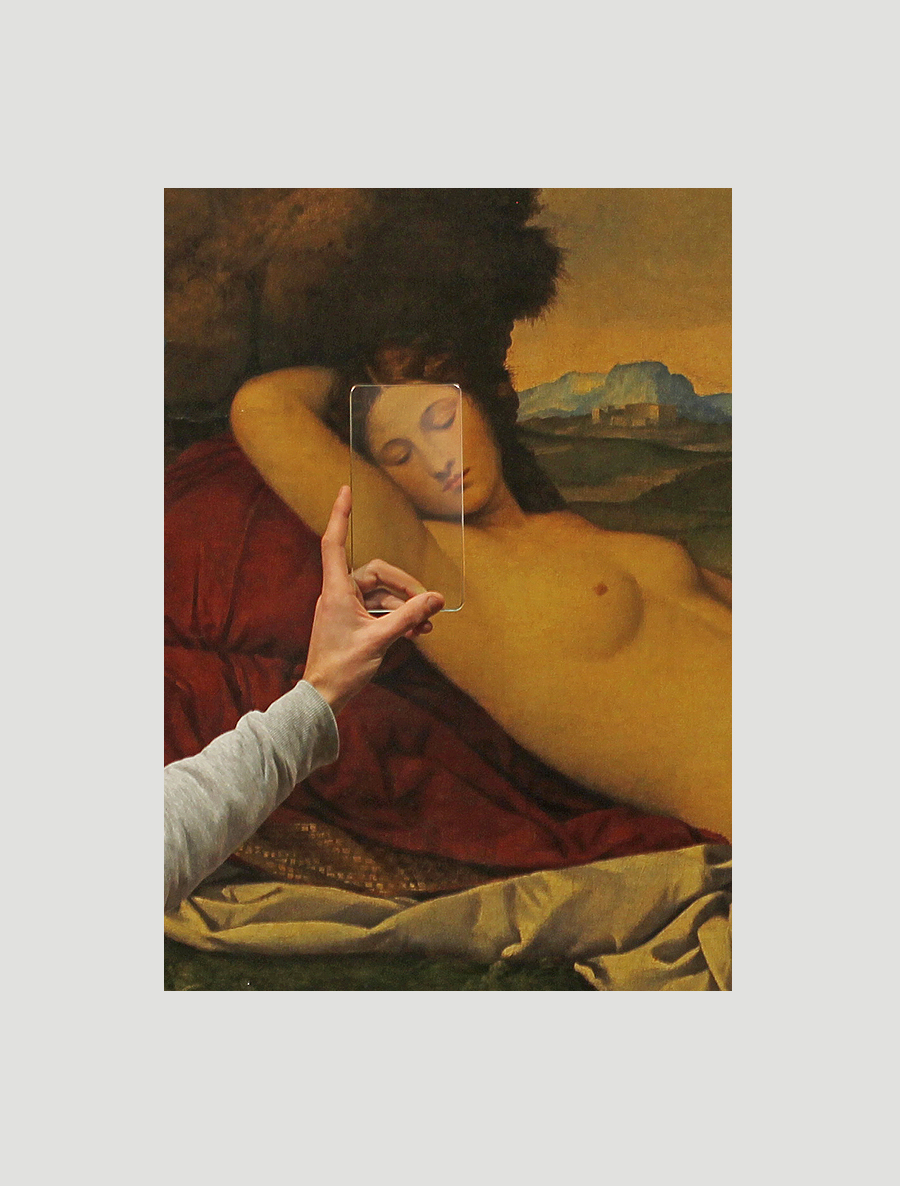

Against the backdrop of this new reality rapidly talking shape, art (even when it is physically produced) begins to gravitate quite perceptibly towards the digital, rather than physical presence. In her 2013 article Flatland, the New York-based critic Loney Abrams problematizes this yearning for online, digital presence. She argues that the art of today can be completely mediocre in reality, but at the same time, it might possess a certain degree of photogenic appeal and look extremely expressive in pictures. The new property is hard-wired into the produced object—an ugly duckling irl, a splendid swan on the screen. The fact that contemporary artists gravitate towards short-lived, fluid, organic materials, such as silicone, wax or foodstuffs and their packages, adds fuel to the fire. And this is not about neglecting the several hundred people-strong public that might see the artwork in real life in favor of the many hundreds of thousands of online viewers that will only see its digital manifestation. Rather, we are talking about the actual transformation of the very logic of the production and dissemination of art that obviously can no longer hold on to the earlier forms of its display, while remaining insensitive to the current changes.

Abrams specifically points out that art is increasingly displayed not in the traditional gallery space but online, in the virtual space of Internet blogs. According to Abrams, the function of art galleries is more and more reduced to a mere backdrop for a photo shoot, while influential blogs about art are taking over the traditional function of the galleries in shaping the audience and staging the context for the perception of art. In the nearest future this tendency will surely enable online blogs to determine the reputation, the context and the estimate for the artwork—the functions that were previously the prerogative of art galleries. The expertise that these blogs can offer, the audience that they are capable of attracting and the aggregation of content—these are the three pillars that will elevate the blogs high above the resources and the potential of any gallery. Over time, the blog itself will no longer need to be present offline: to run an office space, to produce various material goods and souvenirs, like merch, that signify the physically present assemblage or integration point. This transformation will take place once the changes make deep enough inroads that will affect not only the forefront of the art scene but the entire structure of the system of art in all the breadth and depth of its functioning.

Thus, the term flatland used by Abrams denotes the global gravitation of art towards two-dimensional reproduction and consumption. The two-dimensional digital reality of the computer screen is becoming more real than the three-dimensional reality, which due to its volatility, fluidity and constant limitations imposed on our perception, is regarded as far less informative and trustworthy.

“(…)the function of art galleries is more and more reduced to a mere backdrop for a photo shoot, while influential blogs about art are taking over the traditional function of the galleries in shaping the audience(…)”

Yet, at the same time, what then has become of blogs? Are they not the new form of an art gallery now, a gallery, the exact whereabouts of which, as well as its physical layout and size can hardly be deduced, and that is located nowhere and everywhere at once. These characteristics are determined by some constantly changing parameters: the number of cities and countries that have submitted their two-dimensional exhibitions to the gallery, the number of people who saw each of them, the space occupied by the blog on the hosting service, the number of “shares” and “likes” on social network sites. Somewhere, probably, the physically present art objects function as donors of sorts for the most successful images of themselves, reproduced online. The best of these images join the class of Internet memes, and their reproduction is enhanced and prolonged in time. By donor we mean someone other than the original, it gives up part of its material and thereby enables the receiver to lead a fully independent existence. The integrity of the donor is not violated by the gesture of donating. Instead, the integrity divides, like a cell, and is transplanted into the images that the donor has helped to engender. The presence of the donor no longer plays any role in the further process of image disseminating, as every image begins and ends its life online.

Such gallery of a new type functions thanks to the constant interpenetration and symbiotic complementarity of the physical and digital environments in which contemporary art is present. At the same time, due to the speculative character of the legitimacy of such digital images, perceived as full-fledged evidence of the artist’s performance, such gallery itself is fictitious to a very significant extent as its viability unconfirmed and unverified by anything other than the statistics of clicks and reposts. This modality of art distribution that could be called gallery fiction, is characterized by a special approach in the sphere of the production and dissemination of art, which completely replaces the fictitiousness of physical presence with the reality of the digital presence.

Such a logic of the economy of the cultural sphere obviously dictates an entirely different context for the objects, depriving any of the possible contexts of any hope for stability. The context for the perception of any given art object or of a digital image (which is one and the same thing), is constantly changing depending on the exact location on the Internet where you encounter this image. The context can be extremely friendly and conducive to the perception of the object as is, for example, the space of the aggregator website, which provides its expert context for this particular work. It can also be extremely unsuitable for the satisfying perception, consider, for example, facing an art object during a Google search for an apple pie recipe. Such mobility, the impossibility of stabilizing the context results in the complete separation between the context and the art object, the former flaking off of the image completely and the later breaking away from its roots as a pilgrim that forgets about the roots in order to expand his or her presence to the widest and most distant realms.

The so-called Kuleshov effect was conceptualized in the early 20th century with reference to cinematography. It analyzed the defining role of the context in the perception of the situation and since then has long helped to properly “read” art objects. The essence of the effect was manifested in the experiment carried out by the founder of the Russian film school Lev Kuleshov in the 1920s. The viewers were exposed to three fragments of a film with an unchanged actor’s face, shown against three different backgrounds: a plate of hot soup, a child in a coffin and a young girl lounging on a sofa. The viewers concluded that the actor shown in the first fragment was hungry, the actor in the second fragment was mourning his loss and the actor in the third fragment was engulfed by sensual desire. The experiment demonstrated the defining role of the context in eliciting radically different readings of the same object depending on the context that reworks its unchanging outlook beyond recognition. Such context-orientated mode of perception of artworks was extremely user-friendly: regardless of what appeared in front of his or her eyes, the viewer could always be confident that he or she is standing on solid ground that firmly anchors the observed object.

The vigorous struggle of the artists against the contexts that did not suit them for whatever reason ultimately allowed them just to replace one context with another one without adding much to the very technology of perception. Even after art began to be produced on the Internet, changes on the level of technology failed to take place. It quickly became clear where and how to search for and behold art in these new circumstances. Complications arose once the digital and physical environments became equal participants in the presence and dissemination of art. The donor object no longer needed a bond to the physical context in which it was produced, while its multiplying images spilled beyond the confines of a specific site of an Internet-artist or specialized online publications and the like. The context which could be operated rather comfortably by simply grasping the finite series of semantic points, was now falling apart right in front of our eyes and the pilgrim-memes, indifferent to its fate, were drifting away in all possible directions.

The most important element of the stable context of the perception of artworks, whether online or offline, was the fact that the very act of such stabilization guaranteed the sustainability of the spatial and temporal duration of this consumption. Kuleshov’s experimental object, in order to be read, was encircled and squeezed from all sides by the space of the room with soup plates and dead children, while the viewer beholding the object was watching a film that had a beginning and an end. Having passed through this temporal duration, and having assimilated the environment which compressed the observed object, the viewer consumed it, satisfied with the familiar and comprehensible process. Due to the active context, the motionless object was set in motion, thereby obtaining the properties necessary for its recognition. At the same time, given the current gallery fiction mode, the context no longer possesses stable spatial and temporal coordinates and thus can no longer facilitate such recognition. Any object overclocked to the speed of Facebook feed will not be able to capture the viewer’s attention, which means that it will not be replicated and will very soon cease to exist. It is the image itself that is now designed to cover as much space around itself as possible, while expanding and pausing.

“Any object overclocked to the speed of Facebook feed will not be able to capture the viewer’s attention(…)”

The object itself independent from its environment now gets saturated with a certain cinematographic quality whereas previously it was the environment that was cinematographic and passed its properties on to the object. This very same cinematographic quality that enables the object to be both an ugly duckling in physical reality and a splendid swan in the virtual one. Hence, one of the urgent appeals — to take a good look at and to examine the object intently all over again — resonates with the very logic of the functioning of art objects that rejects the choice between their ugly plumage and the beautiful one. The gallery fiction mode, which so often deceives the viewers awaiting the final confirmation of their hypotheses about what they have just seen, works to instill this habit of a scrutinizing gaze. On the one hand, this gallery fiction mode denies each and every preconceived meaning that cannot be formed in a situation of an unstable context. On the other hand, it expands the scope of its operation so much so as to allow only the most attentive viewer to grasp such an “everywhere.” This “everywhere” also means the absence of any command center, of any point where the rays of the image converge and are absorbed. Each structure in this technology seeks to open its architecture, which is the vital precondition for subsequent mem-replication and vitality of all its components.

Perhaps this technology will be able to shape an alternative to the ubiquitously functioning space-time register of capitalistic logic, which has not yet appropriated the systems of decentralized, horizontal dissemination of information. History can emerge at any point in the system, giving rise to an infinite set of narratives, each of which can have an exceptionally high internal elaboration. Within this process one can discern the literal reflection of the technology of the crypto-currencies mining that has already been applied to the emerging system of production and distribution of art. Each image-object, absorbing all sorts of spatial, temporal and semantic characteristics, comes together with a set of other similar images to form its very own narrative, independent from other blochchain-narratives, that constantly renews itself and moves according to its very own logic. We are currently witnessing an endless “mining”, extraction of alternative stories, which prompts one to take a closer look at its fossils: particular art objects that are present somewhere in their material form but are also ubiquitously present online. These objects refuse final answers to the questions about themselves, since their authors participating in such chains know all too well: any answer stabilized and verified through a lengthy experiment can be destroyed at any moment by a sudden attack of apple pies.

Abrams specifically points out that art is increasingly displayed not in the traditional gallery space but online, in the virtual space of Internet blogs. According to Abrams, the function of art galleries is more and more reduced to a mere backdrop for a photo shoot, while influential blogs about art are taking over the traditional function of the galleries in shaping the audience and staging the context for the perception of art. In the nearest future this tendency will surely enable online blogs to determine the reputation, the context and the estimate for the artwork—the functions that were previously the prerogative of art galleries. The expertise that these blogs can offer, the audience that they are capable of attracting and the aggregation of content—these are the three pillars that will elevate the blogs high above the resources and the potential of any gallery. Over time, the blog itself will no longer need to be present offline: to run an office space, to produce various material goods and souvenirs, like merch, that signify the physically present assemblage or integration point. This transformation will take place once the changes make deep enough inroads that will affect not only the forefront of the art scene but the entire structure of the system of art in all the breadth and depth of its functioning.

Thus, the term flatland used by Abrams denotes the global gravitation of art towards two-dimensional reproduction and consumption. The two-dimensional digital reality of the computer screen is becoming more real than the three-dimensional reality, which due to its volatility, fluidity and constant limitations imposed on our perception, is regarded as far less informative and trustworthy.

The essay above was written by Natalya Serkova, philosopher, art theorist, co-founder of TZVETNIK. Featuring Tilman Hornig’s GlassDevices