Emma Hazen in conversation with

ALEX ITO

October, 2016

FOREWORD &

INTERVIEW:

Emma Hazen

STUDIO

PHOTOS:

Sydney Shen

The first studio visit I ever went on was with Alex Ito when I was curating an exhibition for my undergraduate thesis. Before the visit I was quite nervous, but I remember Alex was able to talk about his practice with an extreme poise and directedness that eased my anxieties.

He ended up participating in the group show that took place at the now closed artist-run space, AMO Studios. Since then Alex and I have remained friends and have continued to work together. Most recently, I collaborated with Alex and Masami Kubo for their two-person exhibition at the project space I co-run, Kimberly-Klark. I was thrilled to catch up with Alex about his new body of work debuting at his two current solo exhibitions.

You have two current exhibitions, Act I: Crucible’s Nest at AALA Gallery in Los Angeles, and Act II: Carcass and the White Light forthcoming at Springsteen in Baltimore. What was the decision to sequence the projects as a series of acts?

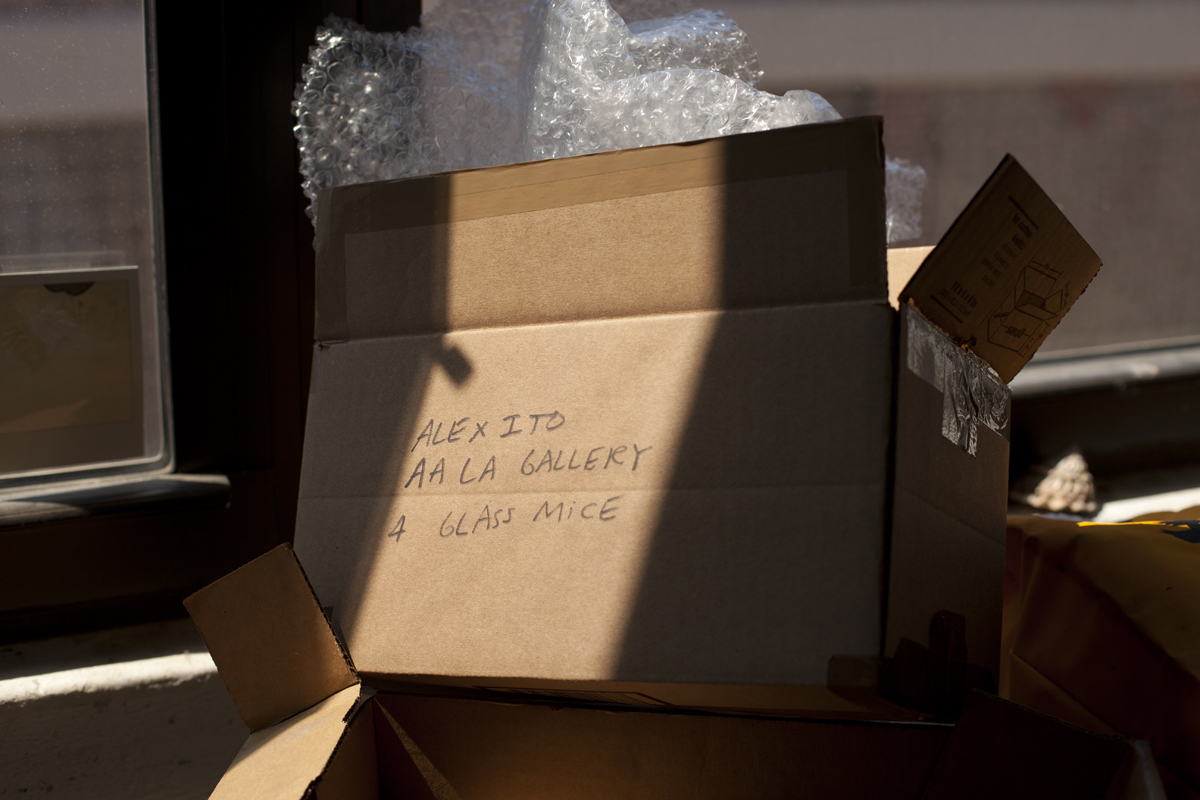

The Los Angeles exhibition sets up the viewer with a more calm and serene space. I’m trying to establish certain media or environments as characters. The concept of a crucible’s nest alludes to a site/object of genesis, transformation as well as violence. In a crucible, materials are extracted, processed and endure traumatic conditions in order to reach a valued functionality. I wanted to place these materials with moments of reflection and mutilation, like how the taxidermy mice are grotesquely translated into glass or how the sofa chair becomes a creature of habit. Act I: Crucible’s Nest is a foundation and a foreshadowing to Act II.

Quickly, the Baltimore show shifts gears as familiar materials (glass, the domestic place, the human body) have transformed in their character. The hierarchies and relationships have transformed. The glass is more sinister, words are more violent, the body is profaned and the viewer is overall approached by a much darker space.

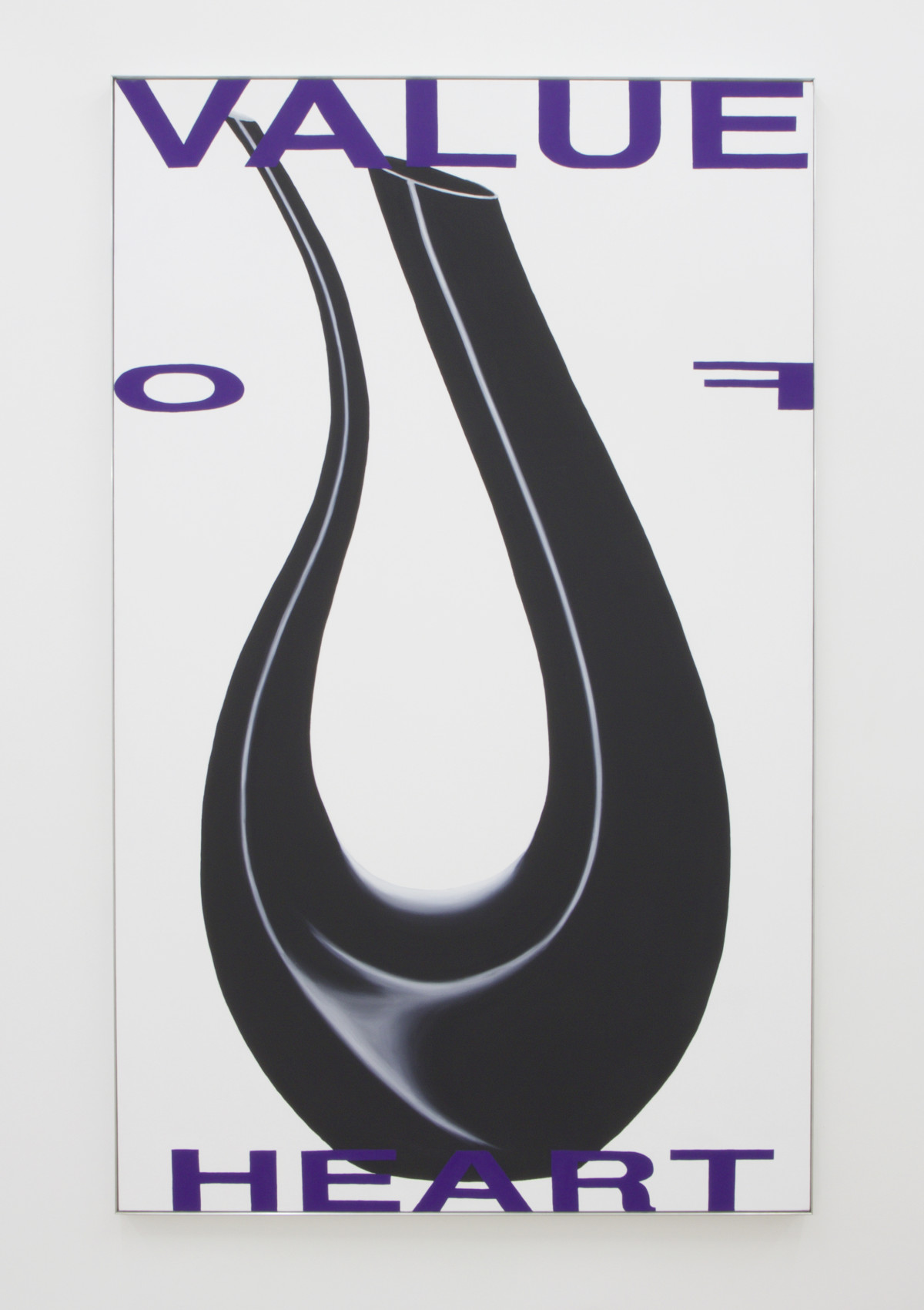

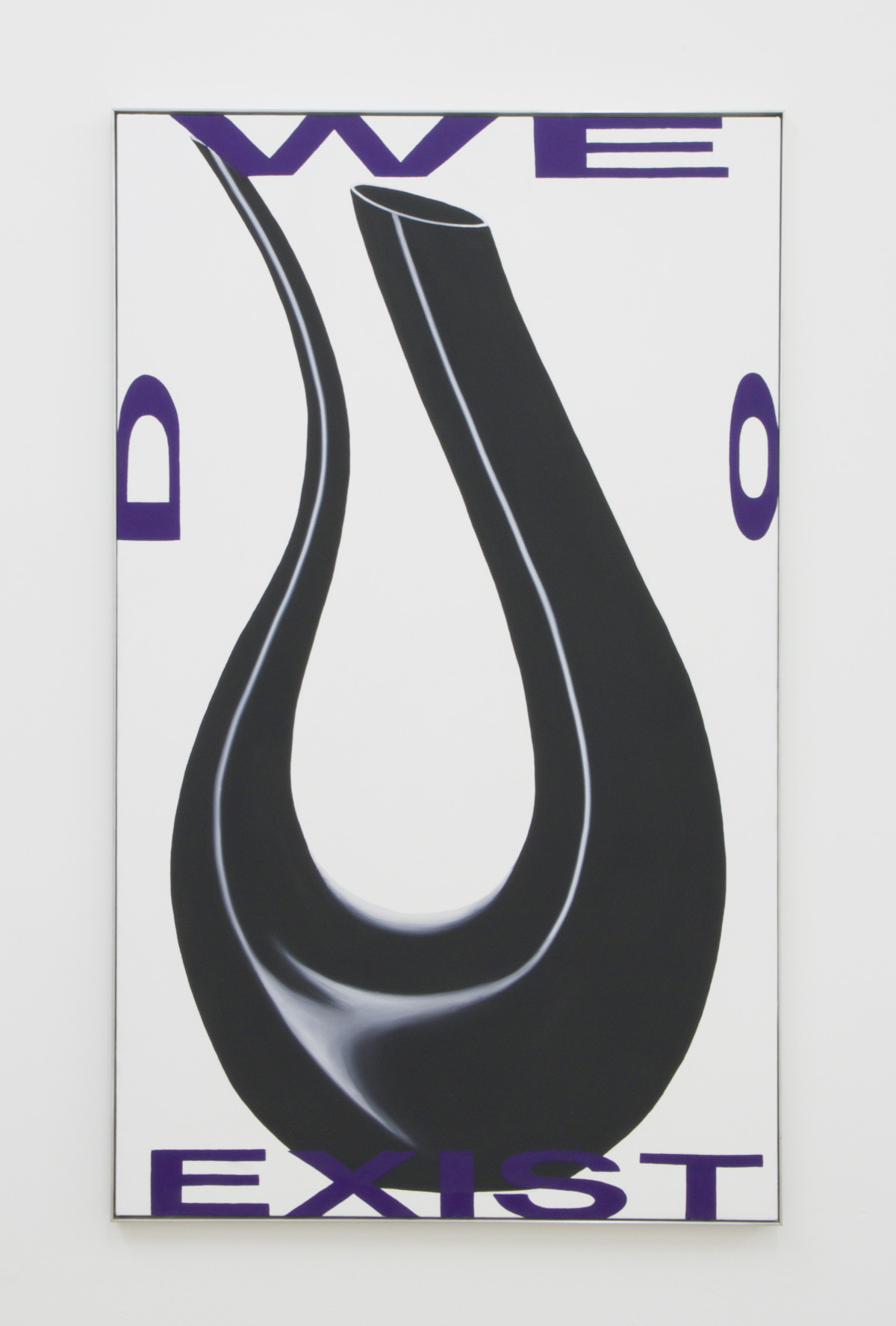

The focus of the paintings for Act I is a black decanter–a glass object produced in a crucible–accompanied by short ambiguous phrases. The texts appear to destabilize the interpretation of the decanter, functioning almost as ominous advertising catchphrases. How do you see the phrases altering the decanter’s signification?

I’ve used vessels like food trays or pachinko bins to allude to a sense of commodified and synthesized consumption. With the decanters, I wanted to speak towards that consumption through a valuation of form. The decanter serves an almost minute utility in how it transforms the taste of wine. Also, what occurs in the decanter can also occur in a regular cup or glass. In a sense, the vessel becomes a luxurious transformation of an existing object, the cup, whose function doesn’t change but the form dictates its status. The decanter becomes a material manipulation of form and the fluids it holds while transforming a hierarchical relationship we share with objects.

I thought this would play a nice and subtle relationship to the text which express a direct challenge to the ways labor and the body become abstracted in the apparatus of industry.

The abstraction of labor and the body are central concepts in your work. Previously, you often had pieces fabricated outside of the studio, distancing the works from your hand and physical labor. For your upcoming exhibitions you have produced two series of paintings. What led to this shift in production and medium?

I have always been interested in creating distance with my work. The materials don’t seem to hold an expressive memory in how industrially produced they are. Many have described my work as cold, arid and even empty. These decisions are meant to reflect the emotional distance I feel with most of everyday life. The aluminum prints I’ve made in the past emphasize a paradoxical muteness of images and words. They are both powerful and invasive while also flat and pious to a law of signs. I wanted an alienation to occur between the viewer and the product/artist with those works. The aluminum prints were utilizing a mechanism of flattening emotional output through images in order to express how many bodies, inside and outside the margins, are silenced through hypomnesis. Bernard Stiegler describes this well in For a New Critique of Political Economy when he says: “their memory has passed into the machine that reproduces gestures the proletariat no longer needs to know- they must simply serve the reproductive machine and thus, once again, become serfs…consumers are henceforth deprived of memory and knowledge by the service industries and their apparatuses”.

The paintings I introduced for these two exhibitions were an expression of my own frustrations and even desires. The flatness of my aluminum prints didn’t seem to be a good fit for this body of work because I wanted to retain a material memory with the work. But paradoxically, that memory of labor and materiality, also becomes passed into a machine through the acts of repetition and commercial art production. Although I personally and physically produced the work, I still become displaced from these paintings. In a sense, the paintings approach the same discussion as the aluminum prints but through a different alley.

Thinking about the works as “critical advertisements,” I wanted to hear more about your interest in advertising as a conceptual framework.

The idea of critical advertisements has been present through most of my work. Whether the prints, the Decanter paintings in Los Angeles or the Hate paintings in Baltimore, the core is to create a critical advertisement.

I’ve always loved the photographs that Irving Penn did for Vogue. The bodies became flat like silhouettes or profiles. Most were all controlled studio images and isolated the body as a thing. You get a neck, a wrist or a pose. They could only be beautiful images through being so violent and possessive over the body. I wanted my work to function similarly to suit my own ideas. Penn became a formal structure for me to refer back to. However, the real feeling for the critical advertisement came from old punk-hardcore printed material and the work of Emory Douglas. Punk-hardcore posters were never about serving a larger audience. It caters to the feelings of a specific community as it intentionally doesn’t want to assimilate.

Emory Douglas was similar and in many ways much more powerful. I remember being in highschool when I saw an exhibition of his work at MOCA Pacific Design Center in Los Angeles. It was the first time I was being educated on the Black Panthers outside of the narrow conversation that occurred in a high school classroom. An image that stuck out to me was an image of an African-American holding an assault rifle with the words “We are determined to change it. We are unafraid”. Although I am distanced from that history, I could not help but be inspired by that image.

Later on, I aligned the visual legacy of Emory Douglas and punk print media with Guy Debord’s idea of detournement. This concept, simply put, utilizes the mechanisms of capitalism against itself. In my current work, I want to engage a critical conversation, an emotional urgency, like Douglas through the framework of what I admired in Penn’s photography in order for the work to fail, and thus critique, itself as a commodity.

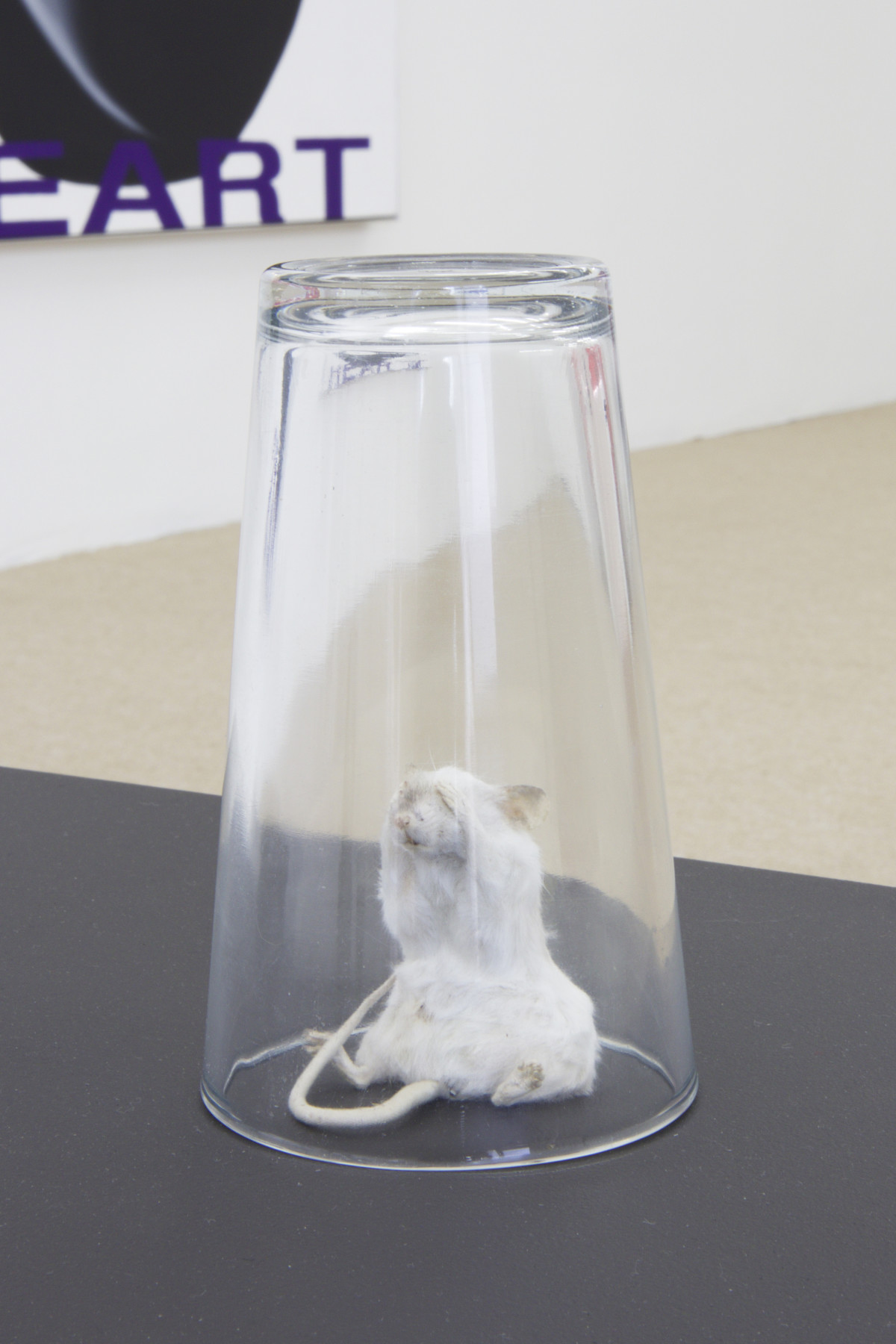

The critique of the failed commodity surfaces in Ghost Rack I & II–sculptures consisting of commercial displays of abnormal objects such as taxidermied mice and virus-like glassworks. At times moving towards the uncanny, I see the pieces alluding to mechanisms of control, such as an animal-testing laboratory, or impending chaos, from a supervirus for example.

I used taxidermy mice in a piece I exhibited in Vienna at Franz Josefs Kai 3 titled The Principles of Hope (The End). In that piece, the mice alluded to a controlled life force within the sparse industrial landscape. Looking like lab mice, they became moments of empathy as well as pathos within the arid industrial landscape.

For the Ghost Rack pieces in Los Angeles, I wanted to create a similar effect but condense the landscape into a product structure, something that the mice would struggle to navigate. The industrial structure works against the mice, similarly to Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times.

The glass displayed on the structures poorly mimic the mice in form and present it in a delicately grotesque fashion. At the time, I was looking at images of objects left over from the atomic bombings and shadows burned into the cement from the explosions. I wanted to think of this transformation from a reductive standpoint of how a machine, both technical and social, can reduce the body to birth something Other.

The Ghost Rack pieces illustrate a machinic mirror by putting together two objects reflecting and refracting each other as product, organism and trauma.

The sculpture for Act II, I’ve only ever known evil, consists of a recumbent figure dressed in a bodysuit of violent imagery with another virus-like glasswork emerging from its torso. Does the piece build upon the Ghost Racks?

Yes, totally. Like when I was describing the succession of characters between the two shows, I’ve only ever known evil is a development to the Ghost Rack pieces that were shown in Los Angeles. Act I was purposely composed and calm whereas Act II would be like the ending scenes in Akira when Tetsuo’s body loses control of itself. The construction of the sculpture was actually influenced from Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989) by Shinya Tsukamoto and the attire of Kuroko theater actors. Kuroko are used in various japanese theaters like kabuki, noh and bunraku as “invisible” actors clad in all black who animate props or non-human characters. In both cases of Tetsuo, Kuroko or atomic history, the body becomes trapped to display and be subservient to production. It reminded me of workers in the industrial theater like e-waste traders in Ghana, online gold miners or the Google workers in Andrew Norman Wilson’s Googleplex series.

The glass object in I’ve only ever known evil emerges from the mannequin’s torso rather attacking the body as a virus or parasite, which seems counterintuitive.

I was originally inspired for the glass by Haruki Murakami’s Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World. In the story a character becomes enamored by and reads the skulls of unicorns which contain “dreams”. In doing so he erases traces of free-will and autonomy from the Town he lives in. The unicorns are sent to die on their own accord as they contently await their disappearance.

I imagined the glass as the skull or remnant of a destructive force, particularly the rapatronic images of the nuclear explosions in the Hate paintings. I wanted to keep this idea of genesis that was present in Act I; that our bodies becomes the vessels and the catalyst for these abstracted objects of violence. The glass attacking the body would illustrate my separation or innocence from the object that I find inaccurate. Even as consumers, our participation or subjugation in the a larger system of exchange reinforce institutions of power and cycles of violence.

The glass becomes both a memory of violence and the polished product of violence birthed from the bodily remains.

When you talk about a “memory of violence,” are you referring to collective or individual memory?

In the case of the objects, I refer more towards a collective memory. A memory embedded in industry and the tasks promoted for the everyday. A memory that we can see when we look back into history and see all that has failed. But of course there is a personal relationship to these ideas circulating in the Springsteen show that came out most with the exhibition we worked on together at Kimberly-Klark with Masami Kubo. The Kimberly-Klark exhibition directly used images and objects from my Japanese-American history, history of the internment camps and an obscured representation of my community within popular culture at the time.

The Springsteen exhibition, along The Principles of Hope (The End) (2015), references the memory of that violence. Some of my grandparents were from Hiroshima and lost everything they had in Japan. It’s interesting to think how they were almost lucky to be imprisoned in the States during that time. A portion of the exhibition text for Act II is influenced by a conversation my childhood friend had with his grandmother who survived the Hiroshima bomb. In many ways, my relationship to this violence is a strange fiction because it is built upon a culture that was lost. My grandparents never spoke Japanese after the war and I was kept away from going to Japanese school by my grandfather. That whole generation doesn’t speak much of those years. I grew up distanced from my Japanese heritage and I think that came from shame and a necessity to assimilate. Through absence the violence is carried on to me.

Although these are personal relationships I have with the work, I feel like I can use them as a jumping off point to invite the voices of other communities to enter the work.

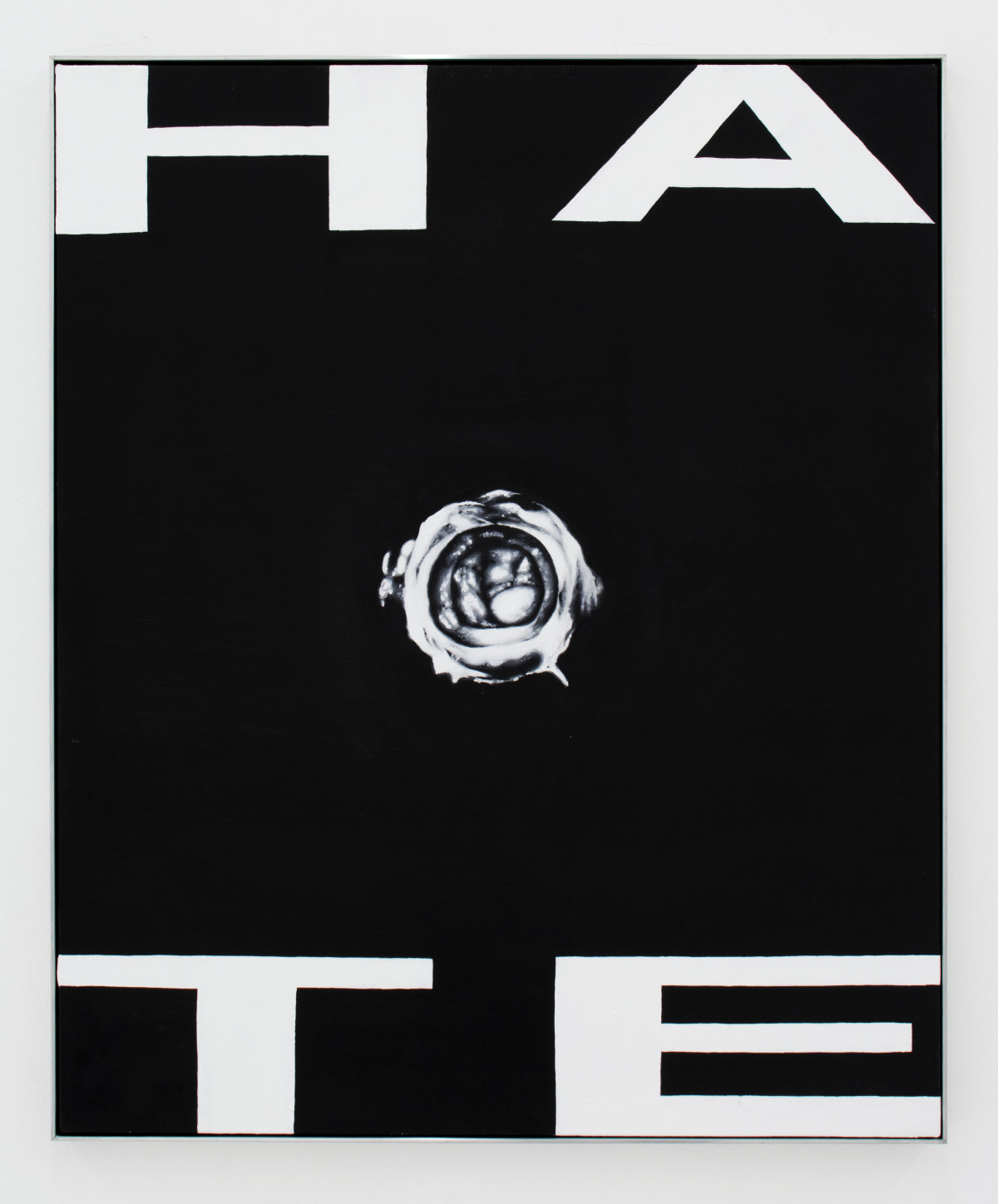

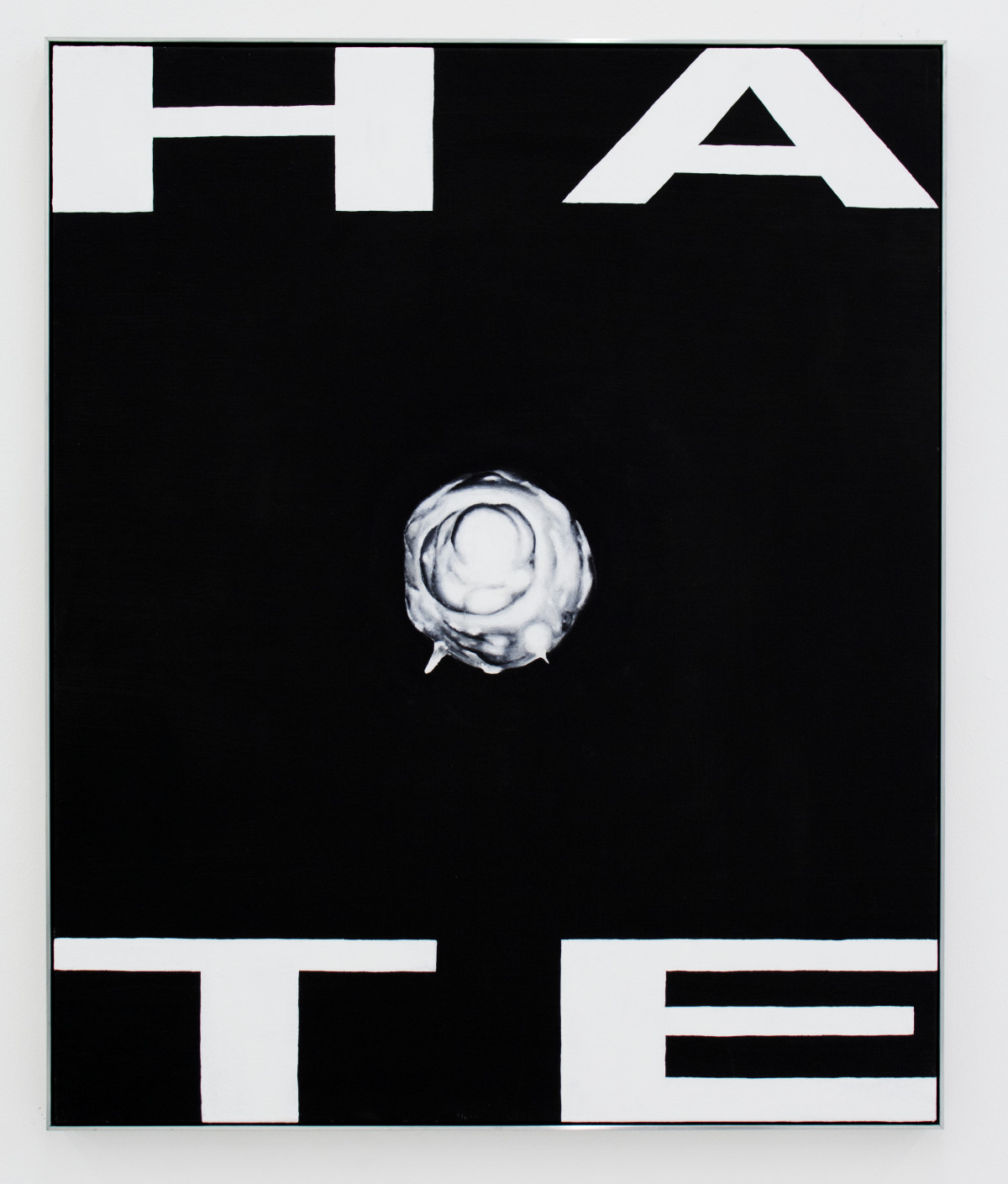

The atomic bomb is a recurrent subject in your work that touches upon a collective memory of violence. For your series of paintings for Act II: Carcass and the White Light, the word “HATE,”–a reference to Robert Indiana’s iconic Pop Art design, “LOVE,”–is lettered over rapatronic images of nuclear explosions. Would you say the explosion images in this series function as polished products birthed from atrocity?

The bomb imagery interests me both for its history and its visual beauty. The images in the Hate paintings are similar to an image I used in Vienna for a piece titled The Principles of Hope (The End). They are renderings of rapatronic photographs of the explosion. In the images, we are looking at the explosion just milliseconds after its detonation. When I first saw them, I didn’t immediately think they were explosions. I thought of amoebas, cells and flowers- basically everything organic that a bomb would destroy.

It intrigued me that I became so obsessed with an image that abstracted such violence. I felt conflicted, similarly to how I was enamored by the Irving Penn images. Both capture composed violence in the abstraction of product: one is composition and the other is a bomb. Both are used for control and manipulation. Through its biopolitical engagement, the image of the atom bomb symbolizes both progress and devastation. Thus, the image is real, becomes alive and must be confronted. The Robert Indiana reference is more of a bridge to the work of General Idea. Their body of work, Image Virus, holds the same communicative spirit of the critical advertisement that I identify with in my own work. I wanted to create an image that would stimulate and direct conversation towards the subject of atomic energy and techno-progressive naivete.

So technology is not going to save us?

The idea of “saving” can become dangerously binary. We are either saved or we are doomed. It’s almost too moral of a question. I can’t have a hard stance for or against technology. Of course technology has physically saved lives and enabled events like the Arab Spring or Occupy. But if we look to historical medical triumphs, a lot are indebted to experiments on slaves and prisoners. New devices and gadgets are loved until they become obsolete and occupy the fields of Ghana, China or India where the e-waste trade is rampant. And of course there is the insanity of the speculative stock market. The world is fueled by an economical necessity to deceive and enslave life. My goal is to raise an awareness towards the participation of consumers, producers and distributors of rhetoric for these industries of everyday life.

Act III, still in production, will be a performance and immersive video installation. At the studio we talked about what the future or progress can be if it is always at someone else’s expense. Do you see a conclusion within this body of work evolving with Act III ?

I wouldn’t say Act III would be a conclusion because where does this all end? Does violence ever go away and how could my “conclusion” potentially continue a history of erasure of the body? Act III is going to be difficult to produce because of how I want to punctuate this exploration. But I guess it doesn’t have to end there, and it could continue or be left open ended.

The performative and video aspects of Act III is to create a more direct dialogue with the body, empathy and the modes of translation and abstraction through non-object based media. Like when I was discussing the role of cinema, the sequencing or choreographing of the body can play an important role in how I claim my responsibility as the maker of a life-inspired, but albeit fictional, history.

Interview by Emma Hazen, writer and co-curator at Kimberly-Klark, NY

Studio photos by Sydney Shen

Act I: Crucible’s Nest

at AALA Gallery in Los Angeles September 10 – October 22, 2016

Act II: Carcass and The White Light

at Springsteen, Baltimore October 15 – December 3, 2016